A home is a human right. Mary Williams talked to those denied it.

An emaciated man crouches on the footpath outside New World supermarket in Dunedin’s North East Valley. He is tearing a sheet of paper into tiny pieces that he places carefully around his feet. People walk by. He accepts an offer of a soft drink, asking for ‘‘Red Bull and bus money. I’m going home soon’’.

People on Dunedin’s streets face the toughest of times. Their plight begs the question, ‘‘Where is home?’’.

As part of our Tough Times series, the Otago Daily Times has investigated where people go, when they have nowhere to go.

We went onto the streets and into the murky world of Dunedin’s notorious, often dilapidated and stinking, boarding houses. We also talked to people seeking respite in the warm embrace of Dunedin’s night shelter.

We listened to life stories blighted, often, by mental illness and addiction. The path to living on the streets, or in boarding houses, often included family breakdowns, domestic violence and other traumatic or criminal events.

We talked to people enduring squalor, with its attendant dangers. We found people who were ill and struggling to self-care — unable to eat regularly or keep themselves and their rooms clean. We also found people living in fear of violence, drug pushing and eviction.

In two better-managed buildings we found higher living standards and evidence of safety — and more hope.

To protect vulnerable people from discrimination, names have been changed. Locations are not named and the faces in photographs have been obscured.

A home is a human right. Mary Williams talked to those denied it.

An emaciated man crouches on the footpath outside New World supermarket in Dunedin’s North East Valley. He is tearing a sheet of paper into tiny pieces that he places carefully around his feet. People walk by. He accepts an offer of a soft drink, asking for ‘‘Red Bull and bus money. I’m going home soon’’.

People on Dunedin’s streets face the toughest of times. Their plight begs the question, ‘‘Where is home?’’.

As part of our Tough Times series, the Otago Daily Times has investigated where people go, when they have nowhere to go.

We went onto the streets and into the murky world of Dunedin’s notorious, often dilapidated and stinking, boarding houses. We also talked to people seeking respite in the warm embrace of Dunedin’s night shelter.

We listened to life stories blighted, often, by mental illness and addiction. The path to living on the streets, or in boarding houses, often included family breakdowns, domestic violence and other traumatic or criminal events.

We talked to people enduring squalor, with its attendant dangers. We found people who were ill and struggling to self-care — unable to eat regularly or keep themselves and their rooms clean. We also found people living in fear of violence, drug pushing and eviction.

In two better-managed buildings we found higher living standards and evidence of safety — and more hope.

To protect vulnerable people from discrimination, names have been changed. Locations are not named and the faces in photographs have been obscured.

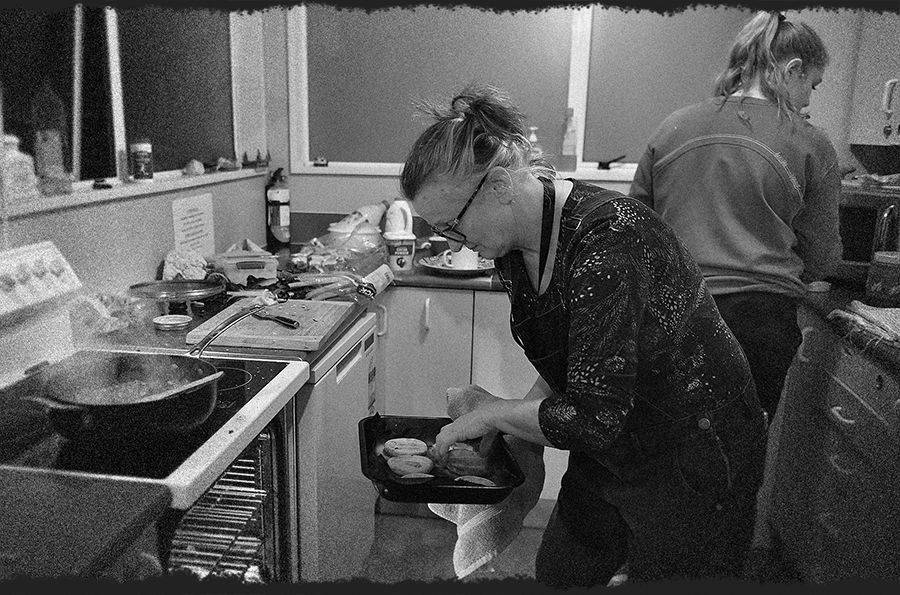

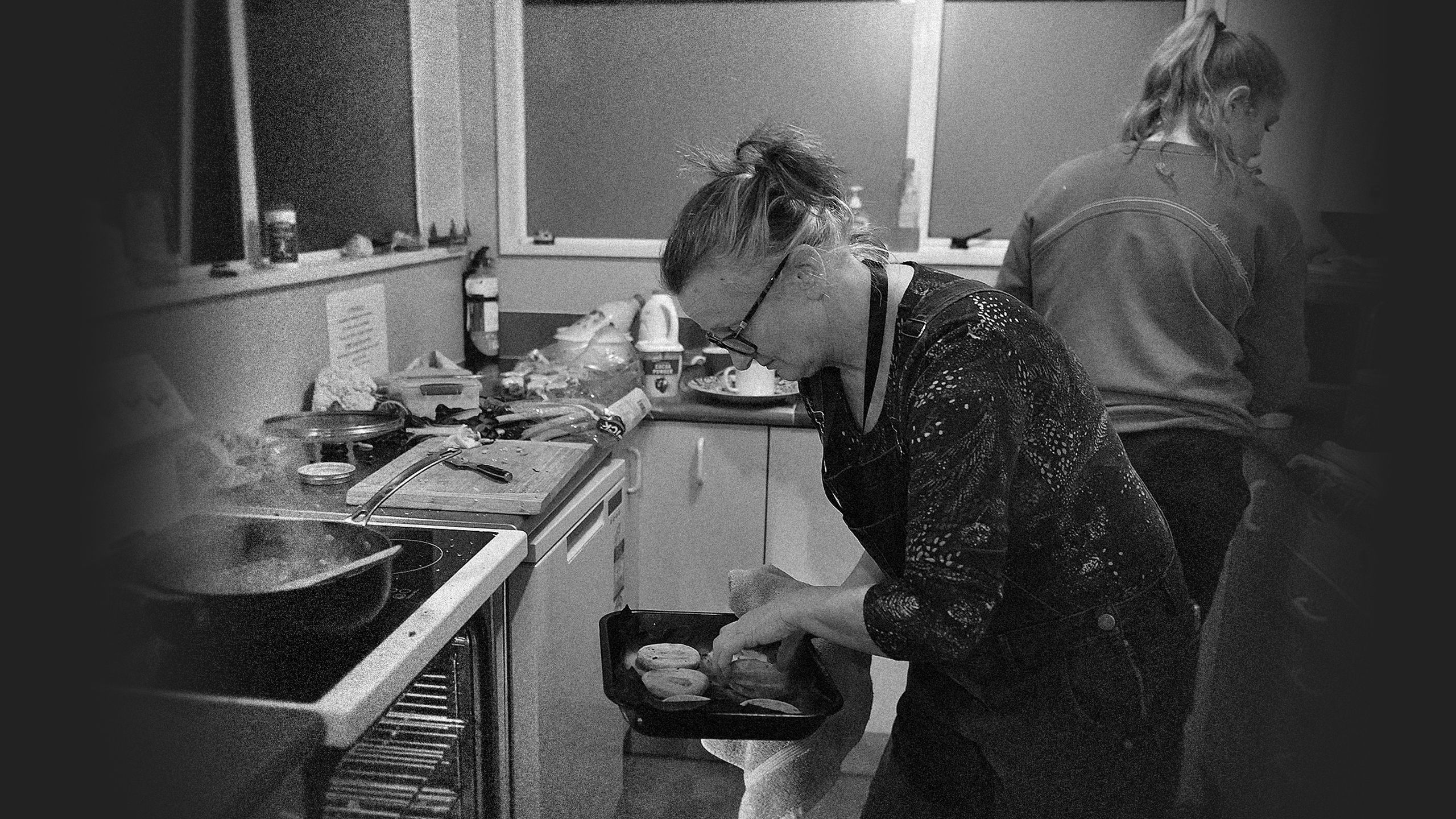

Night supervisor Rose Newburn and volunteer Maddie Newman cook food at the Dunedin Night Shelter.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

On the street

Kate and Shaun

At Dunedin’s night shelter, the two entry rules are no weapons, no inebriation. The latter rule may be bent, if risk to others is unlikely.

There are clean beds, bathrooms and hot food served by supervisors and volunteers — but only for five nights. This is emergency accommodation, with no returns for six weeks.

Kate is at the dining table eating soup. She is a young mother and methamphetamine addict who has been sleeping in a park.

Meth — also known as P in New Zealand — is well known for reducing appetite and causing aggression.

Kate says she didn’t eat when high — existing on ‘‘one energy drink a day’’. Her health suffered terribly. After being locked in a prison cell for the first time, due to an allegation of threatening behaviour, Kate had a wake up call and has not taken meth for three weeks.

‘‘The drug changed me and made me lose reality — I can now see the colour of the trees and ocean again’’. Tears roll down her face. ‘‘I’ve never opened up to anyone like this before. All I want is a house, the kids, the dog — the normal’’.

I feel I am

going to be fed

to the sharks.

Her children are with a relative, while Kate tries to ‘‘sort her life out’’. A room in a boarding house is a likely next step, or a women’s refuge. Her life has included a man who provided a gateway to drugs.

Kate is terrified of boarding houses. ‘‘I have heard the stories. I feel I am going to be fed to the sharks. I don’t go looking for drugs — they find me. I want a fix all the time.’’

Shaun, also at the night shelter’s dining table, says he was the ‘‘druggy from hell’’ as a young adult. He missed his son growing up.

Recently, Shaun’s home was a hospital bed — a member of the public found him on the street ‘‘purple and unconscious. Most people are kind. I’m lucky I didn’t die.’’

A toe had to be amputated — and he has been told he should avoid walking. It’s a hard ask when homeless.

Nevertheless, Shaun is grateful. ‘‘I don’t have an infection.’’

A kind person has donated a pile of new, warm, hiking clothes, displayed across a sofa. Shaun picks out some hiking socks and says thank you.

In the van

Jim

For Jim, home is permanently a vehicle.

A quietly-spoken man in his 60s, he has lived in vehicles since his early 50s, when he lost his house due to difficulties making payments. Jim’s van, parked on a backstreet, appears packed to the roof, with cardboard at the windows.

Jim says his ‘‘recycling’’ has snowballed. ‘‘It’s tricky to stop’’. At night, he says he curls up on the front seat to sleep. It’s the only space left.

During the day he uses a bicycle to visit a local charity day centre, which provides help for people with mental illness and addiction.

There, he fills up a flask with hot water. He uses it, back at his van, for drinks — and to wash. There is a public toilet a few streets away but he has no shower.

Jim dreams of owning a campervan one day and wishes there was a place to freedom camp permanently — a place with a toilet and shower he could use.

However, he adds: ‘‘I’m all right.’’

A charity worker we talk to says: ‘‘The vehicle people are the lucky ones — the ones in tents and doorways are jealous of them.’’

The floor of a resident’s long-term boarding house room is completely covered with a chaotic collection of belongings.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Sinking ship

Mark

Mark — 65— says things can get a ‘‘wee bit past it sometimes’’ at the dilapidated boarding house he lives in, with about 20 other tenants.

The place is in desperate need of repair, filthy, the facilities ancient and limited.

Mark says he has lived here 20 years or so. He drinks vodka. On his own. Another tenant, in his 70s, has lived here nearly twice as long.

This place is like

a shipwreck.

Barely floating . . .

Actually,

we’re sinking.

He describes ‘‘the drugs, 4am noise — and thieves’’. When the worst tenants move on it ‘‘can be more peaceful. But this place is like a shipwreck. Barely floating.’’ He pauses, and considers further. ‘‘Actually, we’re sinking.’’

In his room, there is an appalling stench. Chaotic piles of rubbish, food, and an uncovered dirty mattress, mean the floor has disappeared. It would be impossible to clean without the room being cleared first.

Within the chaos is a fridge freezer and microwave — a common sight in boarding house rooms, to prevent food theft from kitchens. There is no clear, clean surface for food preparation or eating.

Mark talks about issues with keys — losing them and not being reissued with them. But as he points out, this is not a secure place to live anyway.

A passing tenant says the landlord wants to evict Mark — but it’s not clear where he could go. The tenant agrees the house can be ‘‘full of scallywags’’. There was a fight involving a hockey stick.

‘‘No-one gives a shit,’’ he adds, explaining his own history of morphine use, drinking vodka and ‘‘growing up in jail for all kinds of things’’. Violence, guns and kidnapping are mentioned. ‘‘I avoid gangs now.’’

He opens the door to his room — comparatively tidy. There is a theory about tidiness in boarding house rooms that he shares — the tidier the room, the longer the time in prison. Institutions teach order.

He says his family doesn’t like that he lives here. He walks across the corridor and casually breaks into an absent tenant’s room, explaining they are in prison. ‘‘Look how tidy it is.’’

Life after the terrorist

Judy

Judy, in her late 50s, recently got a cat to share her boarding house room. Her arms are covered in raw scratches — she pulls down her sleeves to hide them.

Judy has lived for five years in a sprawling, decaying building with about 20 other tenants. There are poor facilities but she says she ‘‘has it good’’, there’s running water and internet.

Judy is an articulate woman who has worked in communication roles and was married — until her husband tried to kill her. Her mental health suffered and she drank for the first time — ‘‘anything I could get my hands on. Alcohol is too easy to get but the government makes so much money from it.’’

Having a secure, safe roof over your head is a human right. When you are homeless, you can’t recover, rest or study.

She has lived in worse places — including the place with bed bugs, the place with the paranoid stoner landlord, and the time she had to ‘‘shit in a plastic bag’’ when homeless after the Christchurch earthquakes. She lived with a friend for nine months, but eventually it ‘‘didn’t work’’.

‘‘Having a secure, safe roof over your head is a human right. When you are homeless, you can’t recover, rest or study.’’

She says she is ‘‘not ashamed’’ to live here. One bedroom flats require ‘‘a double income’’, pricing her out. Put off by waiting lists, she has not applied for social housing. However, she shows the ODT a floor plan of a social housing flat — and calls for more, with reasonable, stable rents.

‘‘This is all anyone here wants. Instead it can be a race to the bottom.’’

Judy says it can be a race to the bottom.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Judy provides a tour of the building — dingy corridors and a stairwell with a caved in ceiling. There are a few shared toilets, showers, and kitchens that look like they should be in a museum. In strange contrast, someone has planted flowers in a backyard.

There are no communal seating areas. Judy approves. It reduces opportunities to mingle when drunk: ‘‘You can’t fight with yourself.’’

Bad smells seep out from under firmly shut, and numbered, bedroom doors.

Judy points at them and summarises occupants’ challenges — ‘‘mentally ill, physically ill, learning difficulties, hoarder’’.

Judy says a tenant, known for being drunk, high on drugs, violent, and in and out of prison, ‘‘terrorised’’ residents causing ‘‘chaos’’, before dying here. The death brought relief. ‘‘Our terrorist was gone. His ghost still lingers, but the house functions now.’’

Judy describes other incidents. A male tenant masturbated in front of school girls. A female prostituted for gambling money — but when she got a sexually transmitted disease, the antibiotics disrupted her antipsychotic drugs, resulting in noisy nights.

‘‘There just aren’t enough hospital beds for the mentally ill. But it’s also important people remain in the community and not all be pushed into institutions, unable to visit day centres.’’ The house has recently been peaceful.

When asked how she has put up with all the challenges, Judy says: ‘‘I see them as people.’’

Death on the corridors

Chris

At Chris’ dilapidated, large boarding house there are people on ‘‘done’’ — a medical programme that dispenses methadone daily, to help opiate addicts mitigate their cravings.

Chris, in his 50s, says his cravings wake him at 5am every day — but he must wait until 9am to collect his dose at the pharmacy.

Understanding what he says requires patience. Once a promising university student, he now has challenges forming words coherently. He can still cook, however. He is in a basic, tatty kitchen baking scones when we meet. It feels an unusual sight here.

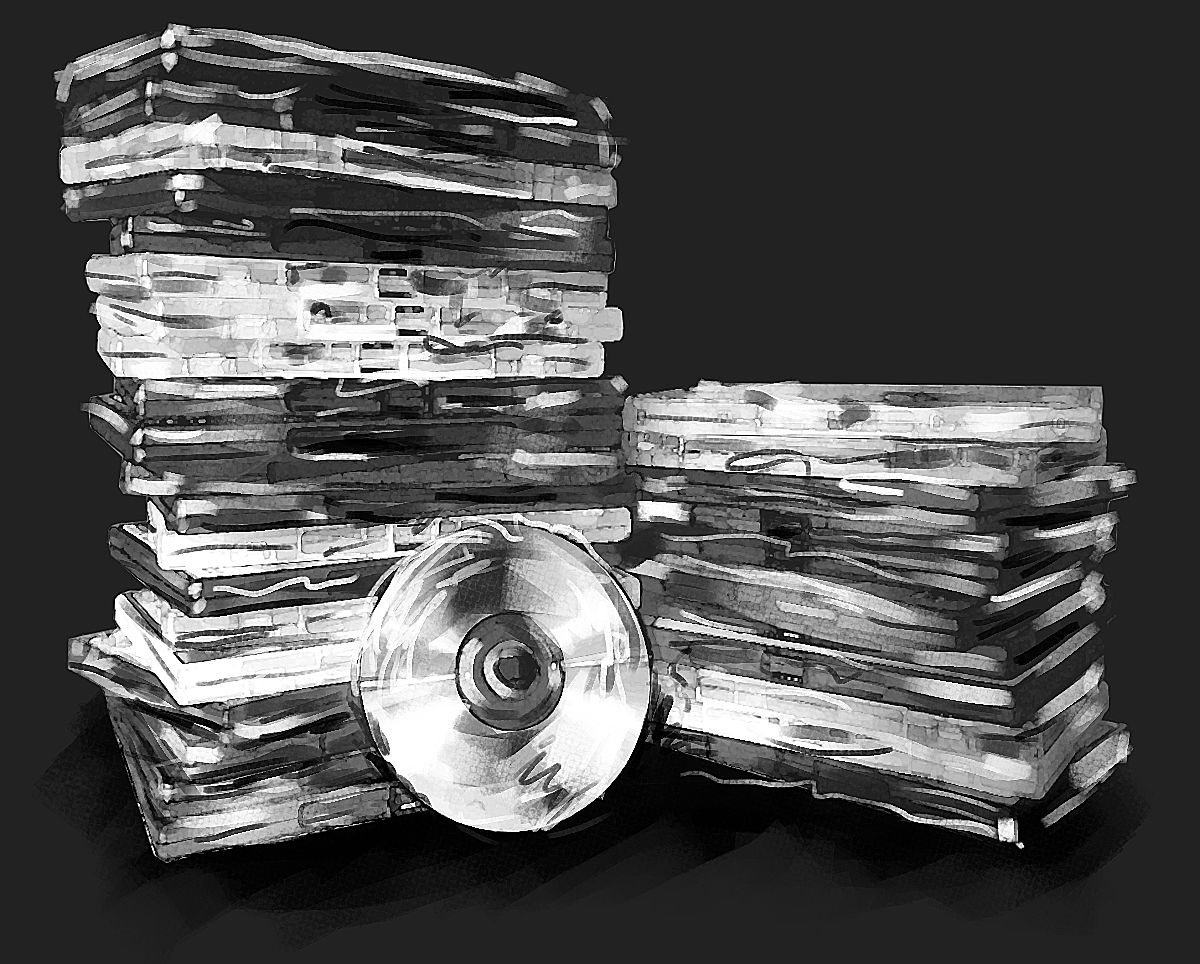

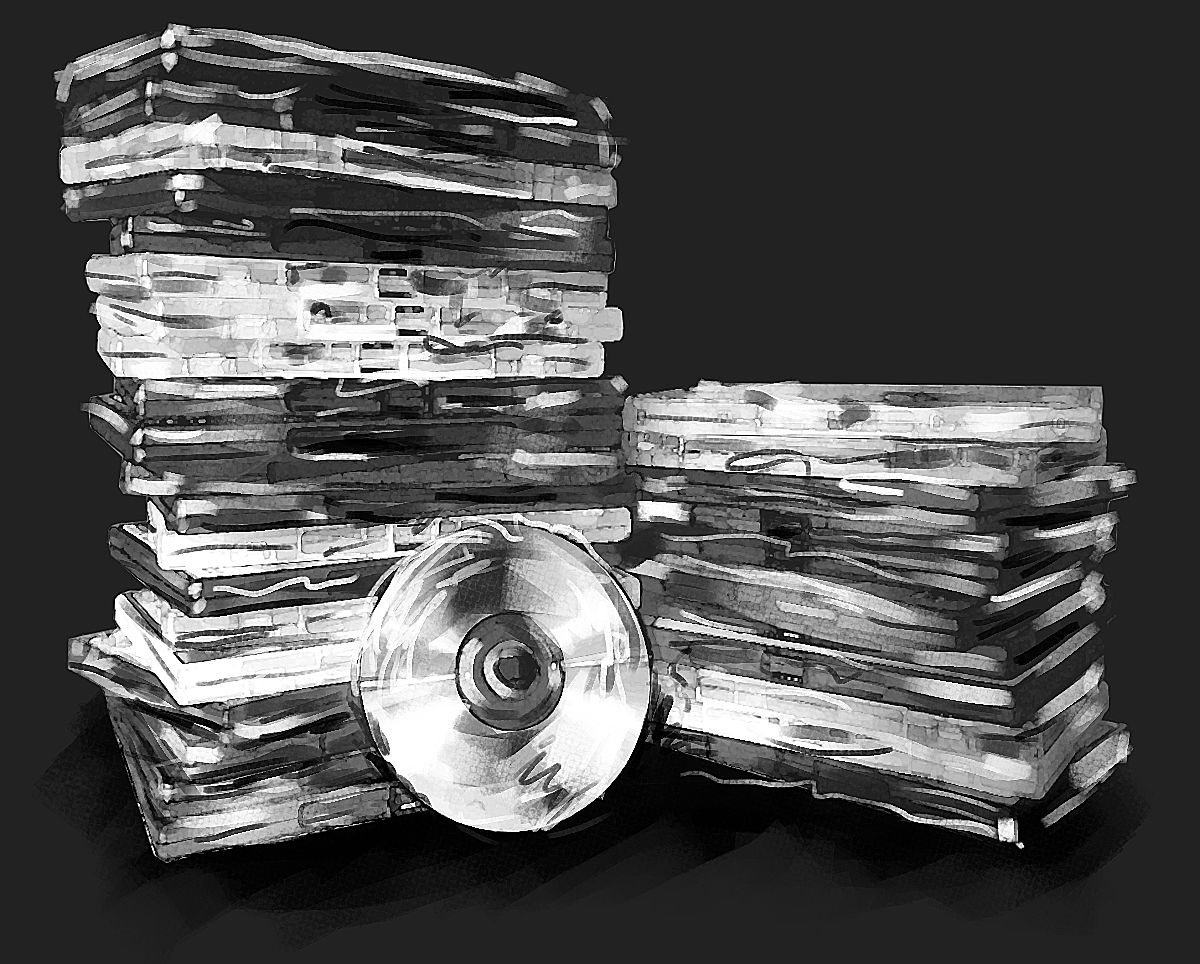

Chris’ room, however, is not an example of domestic order. He hoards. His room is piled high with toys, DVDs and other objects. It is reminiscent of an op shop store cupboard. He says he once had a clear out — motivated by a mice infestation. He caught more than a dozen mice over two days.

He wishes he could afford plastic boxes to protect his things and would welcome a cleaner. ‘‘But it would be a hell of a job.’’

‘‘I meant to just come here and get it together and move on,’’ he says. He was recently astounded to be told by his landlord that he has been here more than a decade. ‘‘I didn’t see that coming.’’

Life in boarding

houses isn’t pretty

and it’s got worse.

He talks of death on the corridors. He thinks one death was caused accidentally by ‘‘mega dosing’’ — taking strong prescription painkillers, bought on the streets, on top of ‘‘done’’.

There was also the alcoholic tenant with emphysema — found days after his death in his room, having ‘‘dissolved’’ into the mattress. ‘‘It’s sad, sad, that it took so long for people to know’’.

‘‘Life in boarding houses isn’t pretty and it’s got worse. The government promised to build houses and put money into mental health — where is it? There is no way in hell people in here are getting the support they need.’’

He mentions a boarding house — once a low-rent backpackers — that he thinks is closing. ‘‘Where will the people who live there go?’’

No place for the young

Josh and Zack

At another grim-looking boarding house a young man in his early 20s stands on the doorstep despite the cold, entertaining a passing mate. There is no communal living room inside.

It is a cloudy day, but Josh wears his sunglasses like a morning-after rock star. His mouth smiles at the corners. Asked if he has done any prison time, he says no, but doesn’t seem to rule out that it could happen.

He has ‘‘avoided doing rehab by dialing down the drugs’’ — MDMA, ketamine and straight spirits — but still uses ketamine, at a cost of about $120 for a supply that ‘‘stretches’’ over a couple of days.

He also drinks beer and takes anti-depressant medication. He has a counsellor but says he can’t go home — dad was ‘‘never in the picture’’ and mum was on hard drugs.

When asked if he would accept more help, to try to get him on a path to employment, Josh looks down at his boots — the soles are peeling off.

‘‘I don’t think I am deserving. I’ve ruined every opportunity, friendship and relationship.’’ He adds that he can’t plan for a future, because he can’t see a future exists.

He politely offers his hand to shake goodbye.

In a building nearby another slim man in his mid 20s warms up milk in a back kitchen. Zack is making chai tea and could easily pass as a chilled out student — but this isn’t a happy student house. It is another forbidding boarding house with many vulnerable and sick tenants.

‘‘We’ve had a few dodgy people come through,’’ says Zack. He mentions a ‘‘very bad junkie — he was sociable though. I was also tackled on the concrete out the back by an alcoholic ex-meth head — he was really irritable.’’

Zack is here because for eight years he spent up to $100 a week on marijuana. He dropped out of university, had a ‘‘messy’’ relationship break up and ‘‘friends took a step back’’. Drug money could have been a deposit on a house, he points out.

He draws a line between his drug use, anxiety and unemployment. ‘‘You can’t work through emotions on weed. You get stuck when there is a life crisis. It can kill motivation and ability to socialise. If you spend a long time not going out, it is a very, very strange experience when you try to do it again.’’

Once you are out of the system, it is difficult to get back in. I’m figuring out how to do it.

Zack says he has kicked his drug habit — 10 months ago — and hopes to find his way into study and a job, but ‘‘once you are out of the system, it is difficult to get back in. I’m figuring out how to do it.’’

When he first tried to stop using weed, he was ‘‘not in a clear head space’’ and decided to have ‘‘one more puff on a cone — but never again. I had a full blown panic attack. I realised that life wasn’t actually going anywhere. I knew I had to take charge.’’

Withdrawal meant cravings and insomnia, but ‘‘since then, everything has really, really improved. Not perfect, but better. I am now comfortable around other people who are smoking and able to say yeah-nah.’’ Recently, he went on a 10-week counselling course and attends a mental health support group.

He opens the door to his room — untidy, but no unpleasant smell. There is a neat row of books. Zack is considering polytechnic and would like to study mental health, having been through the ‘‘dark stuff’’ himself.

‘‘Ultimately, I want to get a job that helps others and be able to present myself in a better light to landlords with nicer buildings.’’

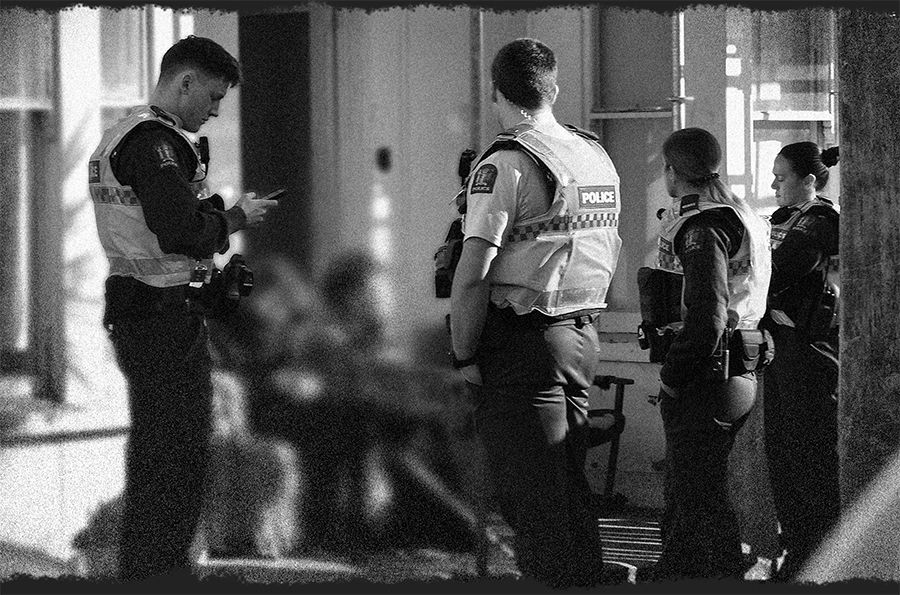

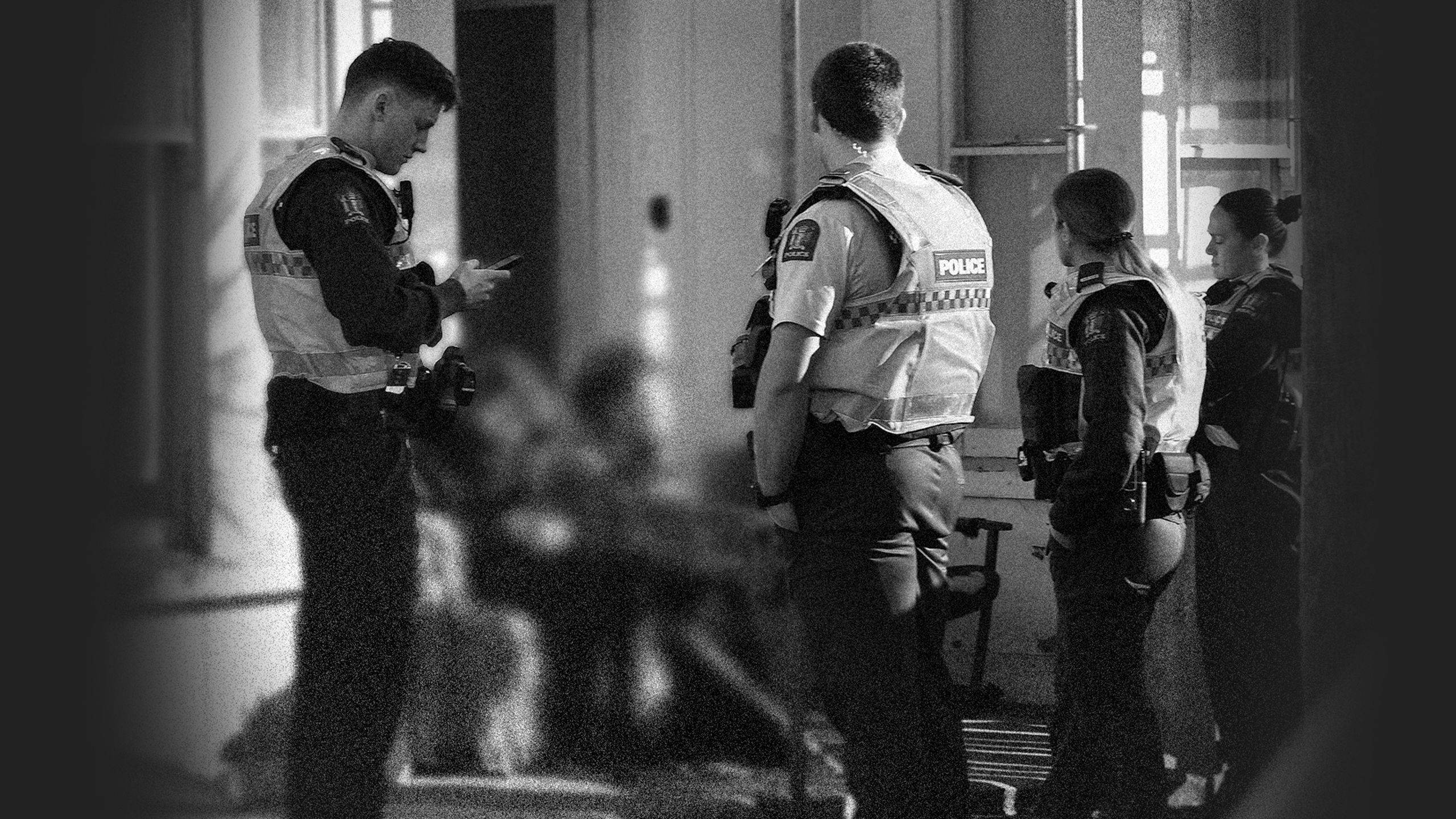

Police talk to boarding house residents after an alleged altercation.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Boarding love

Craig and Anna

Four police officers and a builder are standing around the front of a boarding house. Structurally, it appears poorly. The builder is waiting to get back to work, patching up one of the worst bits.

A passing tenant suggests the building ‘‘might cave in on itself and crumble to the ground. Living here is not for the fainthearted.’’

There has been a spat between a woman and a couple on the floor below. There is no evidence of weapons or major injuries — this time.

After being interviewed by police on the doorstep, Craig and Anna — the couple — say they met in a Dunedin backpackers. ‘‘It’s the quickest place to go when you are homeless.’’

After being asked to leave due to ‘‘issues’’, they say they lived on the streets — in doorways, a carpark and behind a church — before hearing about this place.

Taking the ODT into the building, they show their two rooms — one abandoned, with a strange white mark on the floor that Craig points at. The other room is untidy and big enough for a small bed and a few shelves.

Craig is thin and dirty. Anna leans on a stick. They say they have ‘‘depression — with suicidal tendencies’’ but dispute other mental illness diagnoses they have received.

Anna has injuries, she says sustained through a suicide attempt — after a child was ‘‘taken away’’.

Bad things happen. Anna is my only support, my lifeline and my whole world.

Craig talks about being abandoned by his parents. ‘‘Bad things happen. Anna is my only support, my lifeline and my whole world.’’ He touches Anna’s arm and says they want to get married. ‘‘We break up a lot, but we love each other and we’ll always be together.’’

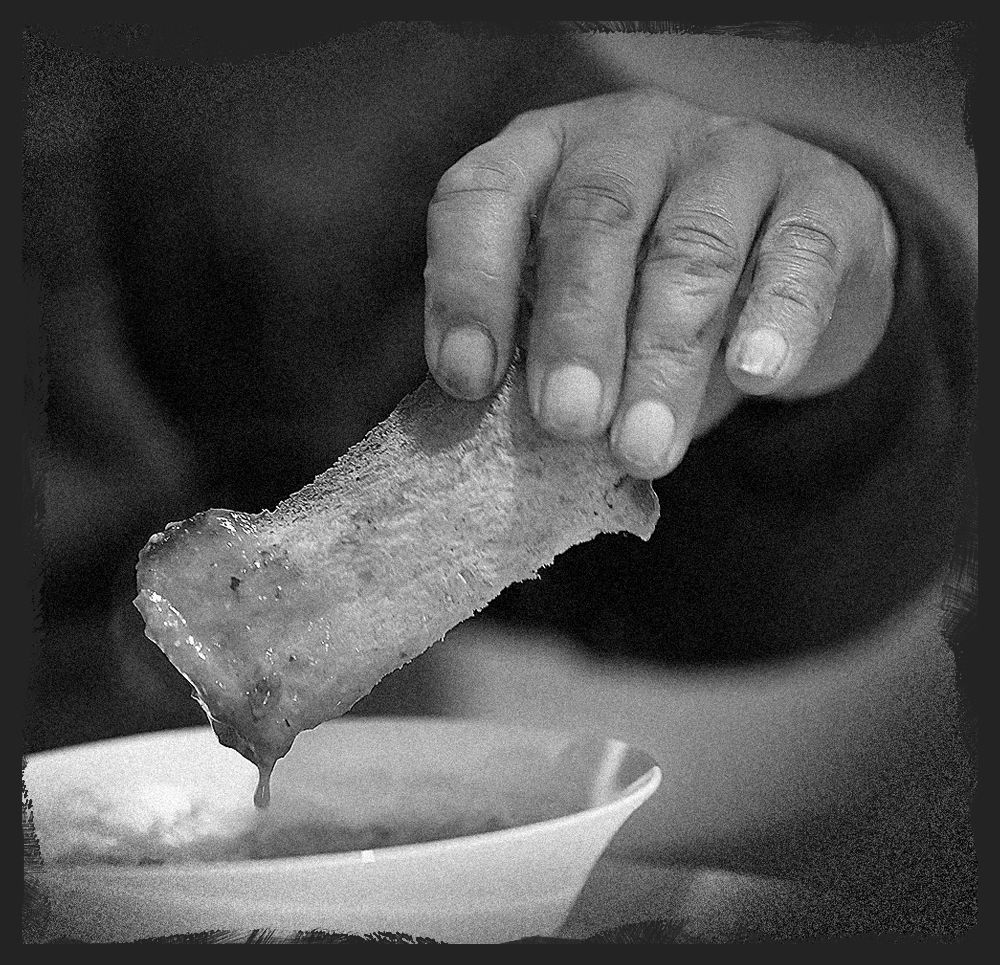

The couple say they don’t eat much during the day — and are sustained by a communal evening meal, cooked by another tenant.

Nigel, the tenant who cooks, has just turned 60 and lived here for five years. He says he is largely able to ‘‘walk away from the fights’’.

Previously a professional, he suffered addiction after a relationship break up — but says he is clean now ‘‘despite the ample opportunities’’.

He has been treated for cancer and has emphysema and arthritis. His room has an external door. The toilet is in a shed nearby. The kitchen and shower are down an outside corridor. This is no place for the sick.

He believes his food helps others survive. ‘‘It takes up my time but makes me feel easier that people here are not going days or weeks without a proper meal.’’

On a second visit, Craig and Anna point to a brick on a top shelf — saying it had been chucked through their window, now boarded up.

Family ties

Denise and Jenny

An unkempt man lurks near a doorway of a boarding house known for being a ‘‘last resort’’.

A woman comes outside wearing a thin dressing gown. She has unkempt hair and missing teeth.

She gives the man a lingering kiss with close body contact — and he gives her a large wad of cash. It’s unclear why.

The woman shows the ODT around the building, then into her small single room, where we find Jenny.

Denise says Jenny is unwell. They had to leave their last place because of behavioural issues.

It is apparent there are problems. Jenny is staring in a mirror, vaping. She starts laughing manically at her reflection. Then laughs again — and again.

The window is broken and boarded up. It happened when they tried to open it, says Denise.

A picture on a shelf says ‘‘family’’. But this is a tragic scene. Denise agrees their situation is not OK — adding they are ‘‘resourceful’’.

Raising the standards

Jane and Dave

Self-care and routine are important to Jane: ‘‘Being kind to yourself includes eating three meals a day, brushing your teeth, showering, doing the dishes and wearing bright clothes. It is so much easier to face the world with confidence and get through the day. It reduces my anxiety and I feel happier.’’

Jane, in her 40s, had her son at 16 — and has suffered from long-term mental health issues including depression, preventing her working.

I’ve heard nightmare stories about other places — I hope people can get out.

She recently turned down an offer of social housing because it’s different here — newly-renovated, with only five tenants. Jane says: ‘‘I’ve heard nightmare stories about other places — I hope people can get out.’’

Her second reason for staying is company. Jane understands isolation and subsequent loneliness can be the enemy of mental health and describes the house as social and functioning. There are barbecues and music sessions — the Bee Gees and Queen, Jane says.

‘‘My worst fear is to live on my own. This boarding house is cool and works for us. Good mental health isn’t just chemical. It is about connections with other people.’’

She talks about stigma around mental illness. ‘‘It is a huge paradox that the most important part of civilisation — mental health — is treated like the least important.’’

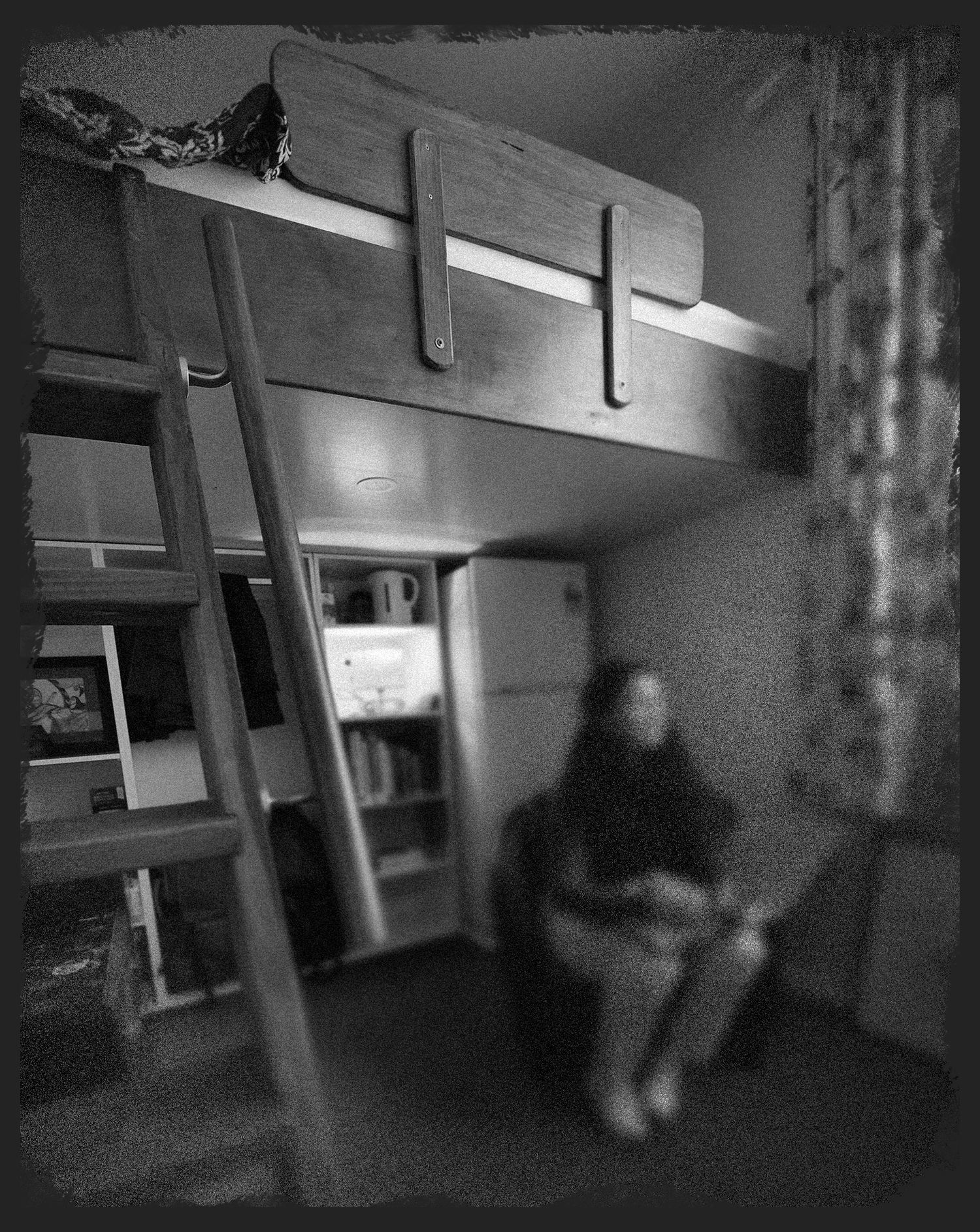

Her room is small. Her bed is up a ladder, but she doesn’t mind. It is a clean and cosy living space. She describes it as ‘‘the future’’ in a time of housing crisis. ‘‘Simple can also be best for people’’, she says — particularly if they are struggling with mental health issues.

The system lacks

aftercare. They

prescribe the

medication but not

the life support.

Jane attributes poorer boarding houses to a government reliance on the private sector, that has failed. ‘‘The system lacks aftercare. They prescribe the medication but not the life support.’’

She hopes she will continue on an upwards path — and work as a mental health advocate in her 50s. ‘‘I want to demonstrate that the housing and support I have received means I can go on to support others.’’

Jane is grateful for her story being shared. ‘‘I have always wanted a voice. Mental illness is such a horrible thing — people are still in the dark about it.’’

Dave, in a room just along from Jane’s, is in his 60s and has spent two years in boarding houses after his relationship broke down. He was working, but then had a ‘‘meltdown’’.

After several mental illness diagnoses, he is currently being reassessed and working on ‘‘cutting back’’ alcohol — which has been ‘‘too much’’.

Dave agrees the standard of the building and tenants are good. ‘‘You can interact with people. The kitchen is spotless, because the person before has cleaned it.’’ He enjoys the music.

Our little group functions well. Anyone can put on a pretty face for five minutes but the mental health system releases people onto the streets who shouldn’t be on the streets — people who piss on the sheets, shit on the floor but also may have outbursts of violence.

A room here remains empty. Dave says it is vital any new tenant is a good fit, to sustain the safety and wellbeing of the other tenants. ‘‘Our little group functions well. Anyone can put on a pretty face for five minutes but the mental health system releases people onto the streets who shouldn’t be on the streets — people who piss on the sheets, shit on the floor but also may have outbursts of violence.’’

He mentions a nasty incident involving a former tenant, no longer in the house. A table was smashed up. The police were called.

‘‘We don’t need or want that. Our rights matter. We all have a right to be here — and be heard.’’

Page design and illustrations: Mathew Patchett

Photos: Stephen Jaquiery

READ MORE:

Night supervisor Rose Newburn and volunteer

Maddie Newman cook food at the Dunedin Night Shelter.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

On the street

Kate and Shaun

At Dunedin’s night shelter, the two entry rules are no weapons, no inebriation. The latter rule may be bent, if risk to others is unlikely.

There are clean beds, bathrooms and hot food served by supervisors and volunteers — but only for five nights. This is emergency accommodation, with no returns for six weeks.

Kate is at the dining table eating soup. She is a young mother and methamphetamine addict who has been sleeping in a park.

Meth — also known as P in New Zealand — is well known for reducing appetite and causing aggression.

Kate says she didn’t eat when high — existing on ‘‘one energy drink a day’’. Her health suffered terribly. After being locked in a prison cell for the first time, due to an allegation of threatening behaviour, Kate had a wake up call and has not taken meth for three weeks.

‘‘The drug changed me and made me lose reality — I can now see the colour of the trees and ocean again’’. Tears roll down her face. ‘‘I’ve never opened up to anyone like this before. All I want is a house, the kids, the dog — the normal’’.

I feel I am

going to be fed

to the sharks.

Her children are with a relative, while Kate tries to ‘‘sort her life out’’. A room in a boarding house is a likely next step, or a women’s refuge. Her life has included a man who provided a gateway to drugs.

Kate is terrified of boarding houses. ‘‘I have heard the stories. I feel I am going to be fed to the sharks. I don’t go looking for drugs — they find me. I want a fix all the time.’’

Shaun, also at the night shelter’s dining table, says he was the ‘‘druggy from hell’’ as a young adult. He missed his son growing up.

Recently, Shaun’s home was a hospital bed — a member of the public found him on the street ‘‘purple and unconscious. Most people are kind. I’m lucky I didn’t die.’’

A toe had to be amputated — and he has been told he should avoid walking. It’s a hard ask when homeless.

Nevertheless, Shaun is grateful. ‘‘I don’t have an infection.’’

A kind person has donated a pile of new, warm, hiking clothes, displayed across a sofa. Shaun picks out some hiking socks and says thank you.

In the van

Jim

For Jim, home is permanently a vehicle.

A quietly-spoken man in his 60s, he has lived in vehicles since his early 50s, when he lost his house due to difficulties making payments. Jim’s van, parked on a backstreet, appears packed to the roof, with cardboard at the windows.

Jim says his ‘‘recycling’’ has snowballed. ‘‘It’s tricky to stop’’. At night, he says he curls up on the front seat to sleep. It’s the only space left.

During the day he uses a bicycle to visit a local charity day centre, which provides help for people with mental illness and addiction.

There, he fills up a flask with hot water. He uses it, back at his van, for drinks — and to wash. There is a public toilet a few streets away but he has no shower.

Jim dreams of owning a campervan one day and wishes there was a place to freedom camp permanently — a place with a toilet and shower he could use.

However, he adds: ‘‘I’m all right.’’

A charity worker we talk to says: ‘‘The vehicle people are the lucky ones — the ones in tents and doorways are jealous of them.’’

The floor of a resident’s long-term boarding house room is completely covered with a chaotic collection of belongings.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Sinking ship

Mark

Mark — 65— says things can get a ‘‘wee bit past it sometimes’’ at the dilapidated boarding house he lives in, with about 20 other tenants.

The place is in desperate need of repair, filthy, the facilities ancient and limited.

Mark says he has lived here 20 years or so. He drinks vodka. On his own. Another tenant, in his 70s, has lived here nearly twice as long.

This place is like

a shipwreck.

Barely floating . . .

Actually,

we’re sinking.

He describes ‘‘the drugs, 4am noise — and thieves’’. When the worst tenants move on it ‘‘can be more peaceful. But this place is like a shipwreck. Barely floating.’’ He pauses, and considers further. ‘‘Actually, we’re sinking.’’

In his room, there is an appalling stench. Chaotic piles of rubbish, food, and an uncovered dirty mattress, mean the floor has disappeared. It would be impossible to clean without the room being cleared first.

Within the chaos is a fridge freezer and microwave — a common sight in boarding house rooms, to prevent food theft from kitchens. There is no clear, clean surface for food preparation or eating.

Mark talks about issues with keys — losing them and not being reissued with them. But as he points out, this is not a secure place to live anyway.

A passing tenant says the landlord wants to evict Mark — but it’s not clear where he could go. The tenant agrees the house can be ‘‘full of scallywags’’. There was a fight involving a hockey stick.

‘‘No-one gives a shit,’’ he adds, explaining his own history of morphine use, drinking vodka and ‘‘growing up in jail for all kinds of things’’. Violence, guns and kidnapping are mentioned. ‘‘I avoid gangs now.’’

He opens the door to his room — comparatively tidy. There is a theory about tidiness in boarding house rooms that he shares — the tidier the room, the longer the time in prison. Institutions teach order.

He says his family doesn’t like that he lives here. He walks across the corridor and casually breaks into an absent tenant’s room, explaining they are in prison. ‘‘Look how tidy it is.’’

Life after the terrorist

Judy

Judy, in her late 50s, recently got a cat to share her boarding house room. Her arms are covered in raw scratches — she pulls down her sleeves to hide them.

Judy has lived for five years in a sprawling, decaying building with about 20 other tenants. There are poor facilities but she says she ‘‘has it good’’, there’s running water and internet.

Judy is an articulate woman who has worked in communication roles and was married — until her husband tried to kill her. Her mental health suffered and she drank for the first time — ‘‘anything I could get my hands on. Alcohol is too easy to get but the government makes so much money from it.’’

Having a secure,

safe roof over your

head is a human right.

When you are homeless,

you can’t recover,

rest or study.

She has lived in worse places — including the place with bed bugs, the place with the paranoid stoner landlord, and the time she had to ‘‘shit in a plastic bag’’ when homeless after the Christchurch earthquakes. She lived with a friend for nine months, but eventually it ‘‘didn’t work’’.

‘‘Having a secure, safe roof over your head is a human right. When you are homeless, you can’t recover, rest or study.’’

She says she is ‘‘not ashamed’’ to live here. One bedroom flats require ‘‘a double income’’, pricing her out. Put off by waiting lists, she has not applied for social housing. However, she shows the ODT a floor plan of a social housing flat — and calls for more, with reasonable, stable rents.

‘‘This is all anyone here wants. Instead it can be a race to the bottom.’’

Judy says it can be a race to the bottom.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Judy provides a tour of the building — dingy corridors and a stairwell with a caved in ceiling. There are a few shared toilets, showers, and kitchens that look like they should be in a museum. In strange contrast, someone has planted flowers in a backyard.

There are no communal seating areas. Judy approves. It reduces opportunities to mingle when drunk: ‘‘You can’t fight with yourself.’’

Bad smells seep out from under firmly shut, and numbered, bedroom doors.

Judy points at them and summarises occupants’ challenges — ‘‘mentally ill, physically ill, learning difficulties, hoarder’’.

Judy says a tenant, known for being drunk, high on drugs, violent, and in and out of prison, ‘‘terrorised’’ residents causing ‘‘chaos’’, before dying here. The death brought relief. ‘‘Our terrorist was gone. His ghost still lingers, but the house functions now.’’

Judy describes other incidents. A male tenant masturbated in front of school girls. A female prostituted for gambling money — but when she got a sexually transmitted disease, the antibiotics disrupted her antipsychotic drugs, resulting in noisy nights.

‘‘There just aren’t enough hospital beds for the mentally ill. But it’s also important people remain in the community and not all be pushed into institutions, unable to visit day centres.’’ The house has recently been peaceful.

When asked how she has put up with all the challenges, Judy says: ‘‘I see them as people.’’

Death on the corridors

Chris

At Chris’ dilapidated, large boarding house there are people on ‘‘done’’ — a medical programme that dispenses methadone daily, to help opiate addicts mitigate their cravings.

Chris, in his 50s, says his cravings wake him at 5am every day — but he must wait until 9am to collect his dose at the pharmacy.

Understanding what he says requires patience. Once a promising university student, he now has challenges forming words coherently. He can still cook, however. He is in a basic, tatty kitchen baking scones when we meet. It feels an unusual sight here.

Chris’ room, however, is not an example of domestic order. He hoards. His room is piled high with toys, DVDs and other objects. It is reminiscent of an op shop store cupboard. He says he once had a clear out — motivated by a mice infestation. He caught more than a dozen mice over two days.

He wishes he could afford plastic boxes to protect his things and would welcome a cleaner. ‘‘But it would be a hell of a job.’’

‘‘I meant to just come here and get it together and move on,’’ he says. He was recently astounded to be told by his landlord that he has been here more than a decade. ‘‘I didn’t see that coming.’’

Life in boarding

houses isn’t pretty

and it’s got worse.

He talks of death on the corridors. He thinks one death was caused accidentally by ‘‘mega dosing’’ — taking strong prescription painkillers, bought on the streets, on top of ‘‘done’’.

There was also the alcoholic tenant with emphysema — found days after his death in his room, having ‘‘dissolved’’ into the mattress. ‘‘It’s sad, sad, that it took so long for people to know’’.

‘‘Life in boarding houses isn’t pretty and it’s got worse. The government promised to build houses and put money into mental health — where is it? There is no way in hell people in here are getting the support they need.’’

He mentions a boarding house — once a low-rent backpackers — that he thinks is closing. ‘‘Where will the people who live there go?’’

No place for the young

Josh and Zack

At another grim-looking boarding house a young man in his early 20s stands on the doorstep despite the cold, entertaining a passing mate. There is no communal living room inside.

It is a cloudy day, but Josh wears his sunglasses like a morning-after rock star. His mouth smiles at the corners. Asked if he has done any prison time, he says no, but doesn’t seem to rule out that it could happen.

He has ‘‘avoided doing rehab by dialing down the drugs’’ — MDMA, ketamine and straight spirits — but still uses ketamine, at a cost of about $120 for a supply that ‘‘stretches’’ over a couple of days.

He also drinks beer and takes anti-depressant medication. He has a counsellor but says he can’t go home — dad was ‘‘never in the picture’’ and mum was on hard drugs.

When asked if he would accept more help, to try to get him on a path to employment, Josh looks down at his boots — the soles are peeling off.

‘‘I don’t think I am deserving. I’ve ruined every opportunity, friendship and relationship.’’ He adds that he can’t plan for a future, because he can’t see a future exists.

He politely offers his hand to shake goodbye.

In a building nearby another slim man in his mid 20s warms up milk in a back kitchen. Zack is making chai tea and could easily pass as a chilled out student — but this isn’t a happy student house. It is another forbidding boarding house with many vulnerable and sick tenants.

‘‘We’ve had a few dodgy people come through,’’ says Zack. He mentions a ‘‘very bad junkie — he was sociable though. I was also tackled on the concrete out the back by an alcoholic ex-meth head — he was really irritable.’’

Zack is here because for eight years he spent up to $100 a week on marijuana. He dropped out of university, had a ‘‘messy’’ relationship break up and ‘‘friends took a step back’’. Drug money could have been a deposit on a house, he points out.

He draws a line between his drug use, anxiety and unemployment. ‘‘You can’t work through emotions on weed. You get stuck when there is a life crisis. It can kill motivation and ability to socialise. If you spend a long time not going out, it is a very, very strange experience when you try to do it again.’’

Once you are out

of the system, it is

difficult to get back in.

I’m figuring out

how to do it.

Zack says he has kicked his drug habit — 10 months ago — and hopes to find his way into study and a job, but ‘‘once you are out of the system, it is difficult to get back in. I’m figuring out how to do it.’’

When he first tried to stop using weed, he was ‘‘not in a clear head space’’ and decided to have ‘‘one more puff on a cone — but never again. I had a full blown panic attack. I realised that life wasn’t actually going anywhere. I knew I had to take charge.’’

Withdrawal meant cravings and insomnia, but ‘‘since then, everything has really, really improved. Not perfect, but better. I am now comfortable around other people who are smoking and able to say yeah-nah.’’ Recently, he went on a 10-week counselling course and attends a mental health support group.

He opens the door to his room — untidy, but no unpleasant smell. There is a neat row of books. Zack is considering polytechnic and would like to study mental health, having been through the ‘‘dark stuff’’ himself.

‘‘Ultimately, I want to get a job that helps others and be able to present myself in a better light to landlords with nicer buildings.’’

Police talk to boarding house

residents after an alleged altercation.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Boarding love

Craig and Anna

Four police officers and a builder are standing around the front of a boarding house. Structurally, it appears poorly. The builder is waiting to get back to work, patching up one of the worst bits.

A passing tenant suggests the building ‘‘might cave in on itself and crumble to the ground. Living here is not for the fainthearted.’’

There has been a spat between a woman and a couple on the floor below. There is no evidence of weapons or major injuries — this time.

After being interviewed by police on the doorstep, Craig and Anna — the couple — say they met in a Dunedin backpackers. ‘‘It’s the quickest place to go when you are homeless.’’

After being asked to leave due to ‘‘issues’’, they say they lived on the streets — in doorways, a carpark and behind a church — before hearing about this place.

Taking the ODT into the building, they show their two rooms — one abandoned, with a strange white mark on the floor that Craig points at. The other room is untidy and big enough for a small bed and a few shelves.

Craig is thin and dirty. Anna leans on a stick. They say they have ‘‘depression — with suicidal tendencies’’ but dispute other mental illness diagnoses they have received.

Anna has injuries, she says sustained through a suicide attempt — after a child was ‘‘taken away’’.

Bad things happen.

Anna is my only

support, my lifeline

and my whole world.

Craig talks about being abandoned by his parents. ‘‘Bad things happen. Anna is my only support, my lifeline and my whole world.’’ He touches Anna’s arm and says they want to get married. ‘‘We break up a lot, but we love each other and we’ll always be together.’’

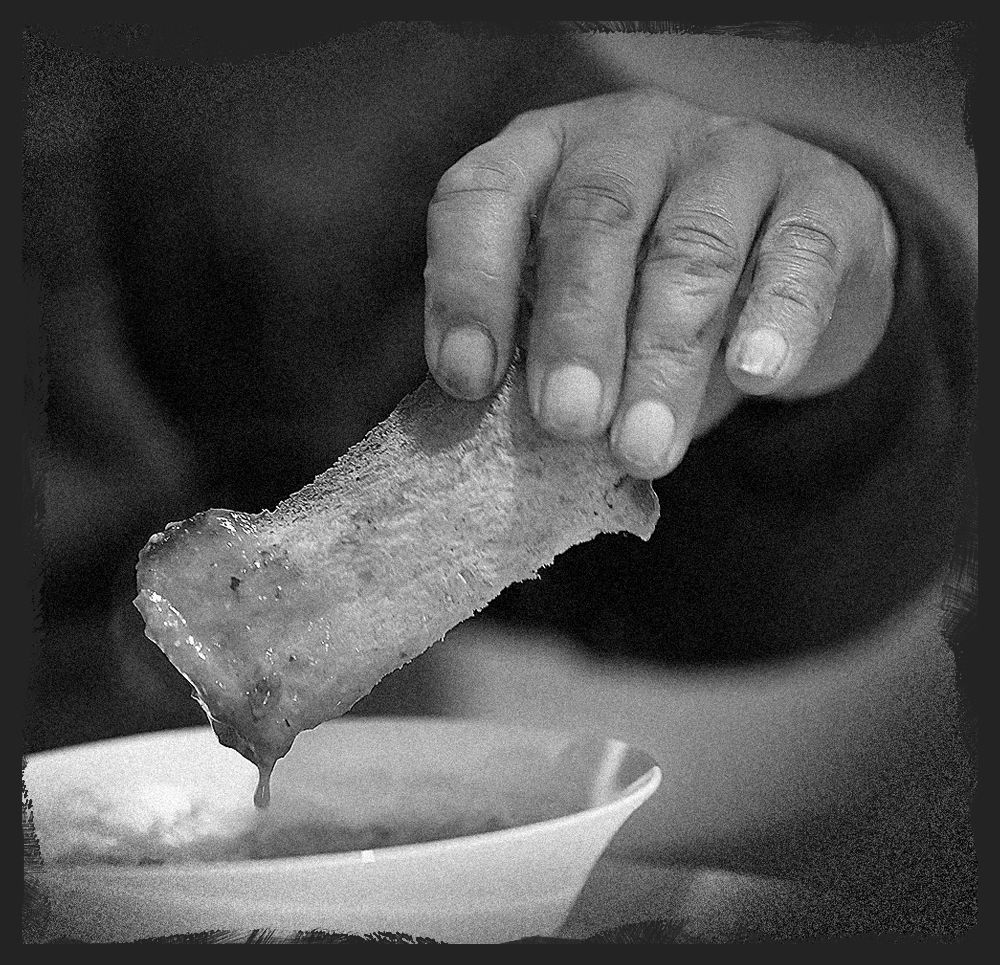

The couple say they don’t eat much during the day — and are sustained by a communal evening meal, cooked by another tenant.

Nigel, the tenant who cooks, has just turned 60 and lived here for five years. He says he is largely able to ‘‘walk away from the fights’’.

Previously a professional, he suffered addiction after a relationship break up — but says he is clean now ‘‘despite the ample opportunities’’.

He has been treated for cancer and has emphysema and arthritis. His room has an external door. The toilet is in a shed nearby. The kitchen and shower are down an outside corridor. This is no place for the sick.

He believes his food helps others survive. ‘‘It takes up my time but makes me feel easier that people here are not going days or weeks without a proper meal.’’

On a second visit, Craig and Anna point to a brick on a top shelf — saying it had been chucked through their window, now boarded up.

Family ties

Denise and Jenny

An unkempt man lurks near a doorway of a boarding house known for being a ‘‘last resort’’.

A woman comes outside wearing a thin dressing gown. She has unkempt hair and missing teeth.

She gives the man a lingering kiss with close body contact — and he gives her a large wad of cash. It’s unclear why.

The woman shows the ODT around the building, then into her small single room, where we find Jenny.

Denise says Jenny is unwell. They had to leave their last place because of behavioural issues.

It is apparent there are problems. Jenny is staring in a mirror, vaping. She starts laughing manically at her reflection. Then laughs again — and again.

The window is broken and boarded up. It happened when they tried to open it, says Denise.

A picture on a shelf says ‘‘family’’. But this is a tragic scene. Denise agrees their situation is not OK — adding they are ‘‘resourceful’’.

Raising the standards

Jane and Dave

Self-care and routine are important to Jane: ‘‘Being kind to yourself includes eating three meals a day, brushing your teeth, showering, doing the dishes and wearing bright clothes. It is so much easier to face the world with confidence and get through the day. It reduces my anxiety and I feel happier.’’

Jane, in her 40s, had her son at 16 — and has suffered from long-term mental health issues including depression, preventing her working.

I’ve heard nightmare

stories about other

places — I hope

people can get out.

She recently turned down an offer of social housing because it’s different here — newly-renovated, with only five tenants. Jane says: ‘‘I’ve heard nightmare stories about other places — I hope people can get out.’’

Her second reason for staying is company. Jane understands isolation and subsequent loneliness can be the enemy of mental health and describes the house as social and functioning. There are barbecues and music sessions — the Bee Gees and Queen, Jane says.

‘‘My worst fear is to live on my own. This boarding house is cool and works for us. Good mental health isn’t just chemical. It is about connections with other people.’’

She talks about stigma around mental illness. ‘‘It is a huge paradox that the most important part of civilisation — mental health — is treated like the least important.’’

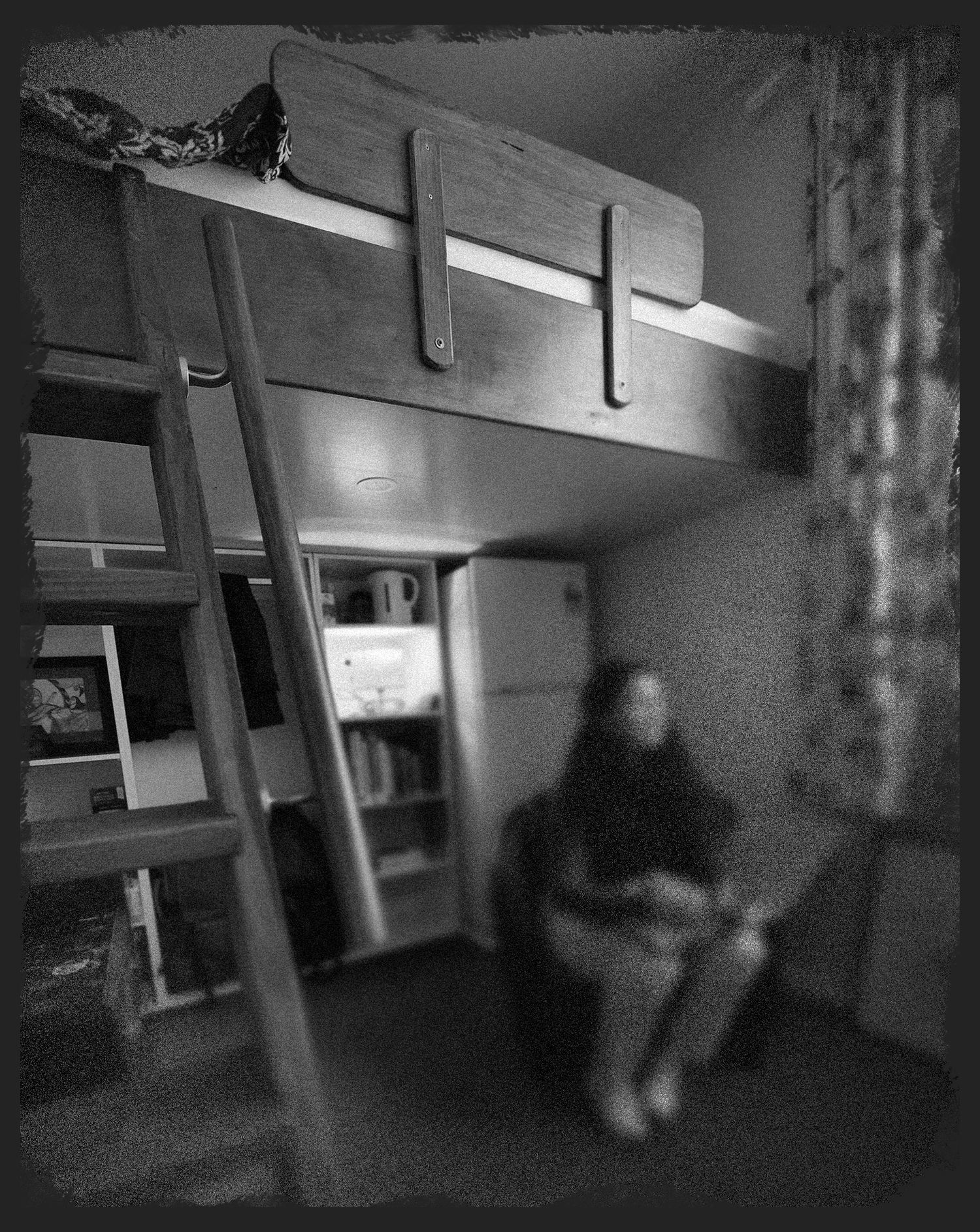

Her room is small. Her bed is up a ladder, but she doesn’t mind. It is a clean and cosy living space. She describes it as ‘‘the future’’ in a time of housing crisis. ‘‘Simple can also be best for people’’, she says — particularly if they are struggling with mental health issues.

The system lacks

aftercare. They

prescribe the

medication but not

the life support.

Jane attributes poorer boarding houses to a government reliance on the private sector, that has failed. ‘‘The system lacks aftercare. They prescribe the medication but not the life support.’’

She hopes she will continue on an upwards path — and work as a mental health advocate in her 50s. ‘‘I want to demonstrate that the housing and support I have received means I can go on to support others.’’

Jane is grateful for her story being shared. ‘‘I have always wanted a voice. Mental illness is such a horrible thing — people are still in the dark about it.’’

Dave, in a room just along from Jane’s, is in his 60s and has spent two years in boarding houses after his relationship broke down. He was working, but then had a ‘‘meltdown’’.

After several mental illness diagnoses, he is currently being reassessed and working on ‘‘cutting back’’ alcohol — which has been ‘‘too much’’.

Dave agrees the standard of the building and tenants are good. ‘‘You can interact with people. The kitchen is spotless, because the person before has cleaned it.’’ He enjoys the music.

Our little group functions well. Anyone can put on a pretty face for five minutes but the mental health system releases people onto the streets who shouldn’t be on the streets — people who piss on the sheets, shit on the floor but also may have outbursts of violence.

A room here remains empty. Dave says it is vital any new tenant is a good fit, to sustain the safety and wellbeing of the other tenants. ‘‘Our little group functions well. Anyone can put on a pretty face for five minutes but the mental health system releases people onto the streets who shouldn’t be on the streets — people who piss on the sheets, shit on the floor but also may have outbursts of violence.’’

He mentions a nasty incident involving a former tenant, no longer in the house. A table was smashed up. The police were called.

‘‘We don’t need or want that. Our rights matter. We all have a right to be here — and be heard.’’

Page design and illustrations: Mathew Patchett

Photos: Stephen Jaquiery

READ MORE: