A Dunedin stalker, whose dogged and bizarre pursuit of a teenage girl plagued her final years of high school, can now be unmasked. The victim tells Rob Kidd about how the ordeal changed her life and about the gruelling fight for justice.

A Dunedin stalker, whose dogged and bizarre

pursuit of a teenage girl plagued her final

years of high school, can now be unmasked.

The victim tells Rob Kidd about how the

ordeal changed her life and about the

gruelling fight for justice.

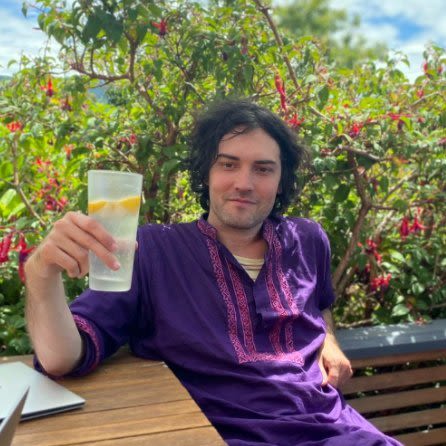

Shane Mulligan cut a meek figure in the dock.

Unshaven and in ill-fitting jeans, a dinky paunch visible beneath a white polo shirt bearing his name, a slight stoop in his posture, hands clasped before him in seeming supplication.

The 35-year-old looked messy rather than menacing.

But Mulligan’s weapons were his words.

Stalker . . . Shane Mulligan was sentenced to intensive supervision after pleading guilty to harassment. PHOTO: GREGOR RICHARDSON

Stalker . . . Shane Mulligan was sentenced to intensive supervision after pleading guilty to harassment. PHOTO: GREGOR RICHARDSON

His sentencing last month marked the end of three years of torment for his teenage victim, during which the IT expert bombarded her and her family with messages, devoted a blog to her and repeatedly defied court orders.

In August last year — on the back of an innocuous 10-minute chat a couple of years earlier — Mulligan proposed to the girl in the form of an eight-page manifesto.

‘‘When I met her, I saw her heart. I knew. She’s the one I actually want. She’s the one I’m not allowed to have. She’s the one I want,’’ he wrote.

Despite her blocking Mulligan’s social media channels and having family members battle to keep him at bay, he persisted.

In a statement to the court, she concisely conveyed the magnitude of the misery he caused.

‘‘Shane has shattered my future.’’

Melee Dowle was under 18 when the stalking started, so her identity was automatically suppressed by law. But at the recent sentencing, she told Judge Jim Large she did not want it.

Ms Dowle wanted vindication.

For all the friends who thought she was lucky to be the subject of such an outpouring of affection, all the teachers who believed it was an overreaction.

They were wrong.

No one else at Ms Dowle’s school had 111 on speed dial, an emergency action plan, a police file number with them at all times and a photo of their stalker lodged with the school office.

She described her final year of school as an ‘‘uphill mountain to climb’’, when she was carrying the psychological burden of an adult man obsessed with her ‘‘lurking in the background’’ of her life.

Ms Dowle had always planned to continue her IT studies at the University of Otago, but the possibility of bumping into Mulligan in Dunedin was too terrifying.

So she had uprooted her life and moved north.

While it put physical distance between them, Ms Dowle said the spectre of her tormentor had followed.

Ms Dowle’s protracted ordeal with Mulligan had an unlikely inception — a coding class run through the church they attended.

The member of the congregation who supervised the sessions, a computer-science academic, said Mulligan was one of his students and he had no hesitation allowing his involvement as a ‘‘demonstrator’’.

During the classes, he never saw any concerning behaviour, he said.

But an obsession was brewing.

Ms Dowle, who was 16 at the time, never even noticed Mulligan and did not recall interacting with him during the coding seminars.

They only conversed once when she was waiting to be picked up from church.

‘‘We spoke for 10 minutes, maybe even less,’’ she told the Otago Daily Times.

‘‘It was mostly me just talking, because when people bring up computers I kind of get excited so I just ramble.’’

However, within hours, Mulligan had found her on Facebook and it began.

It was not so much a charm offensive as an onslaught; messages, dense, sprawling paragraphs in the early hours of the morning, featuring offbeat references to people and topics of which Ms Dowle had no knowledge.

‘‘I just thought it was a part of his eccentric personality,’’ she said.

‘‘I didn’t want to be dismissive.’’

Mulligan mused about private lessons, a trip to Megazone together.

Ms Dowle declined.

But the rejections made little difference.

‘‘I didn’t go to church that frequently, but the times I did, I would sometimes see him in the crowd and usually he was just staring at me,’’ she said.

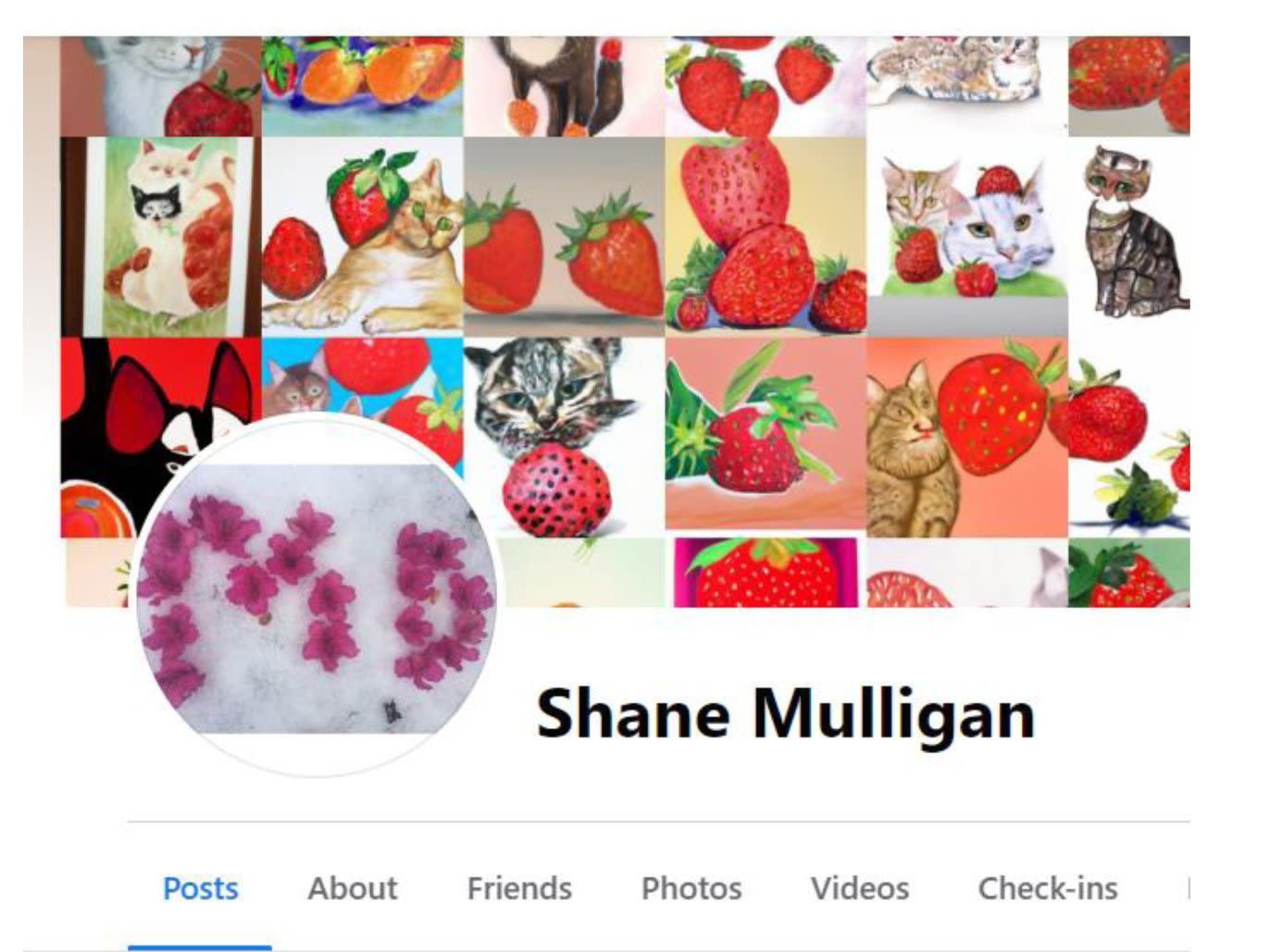

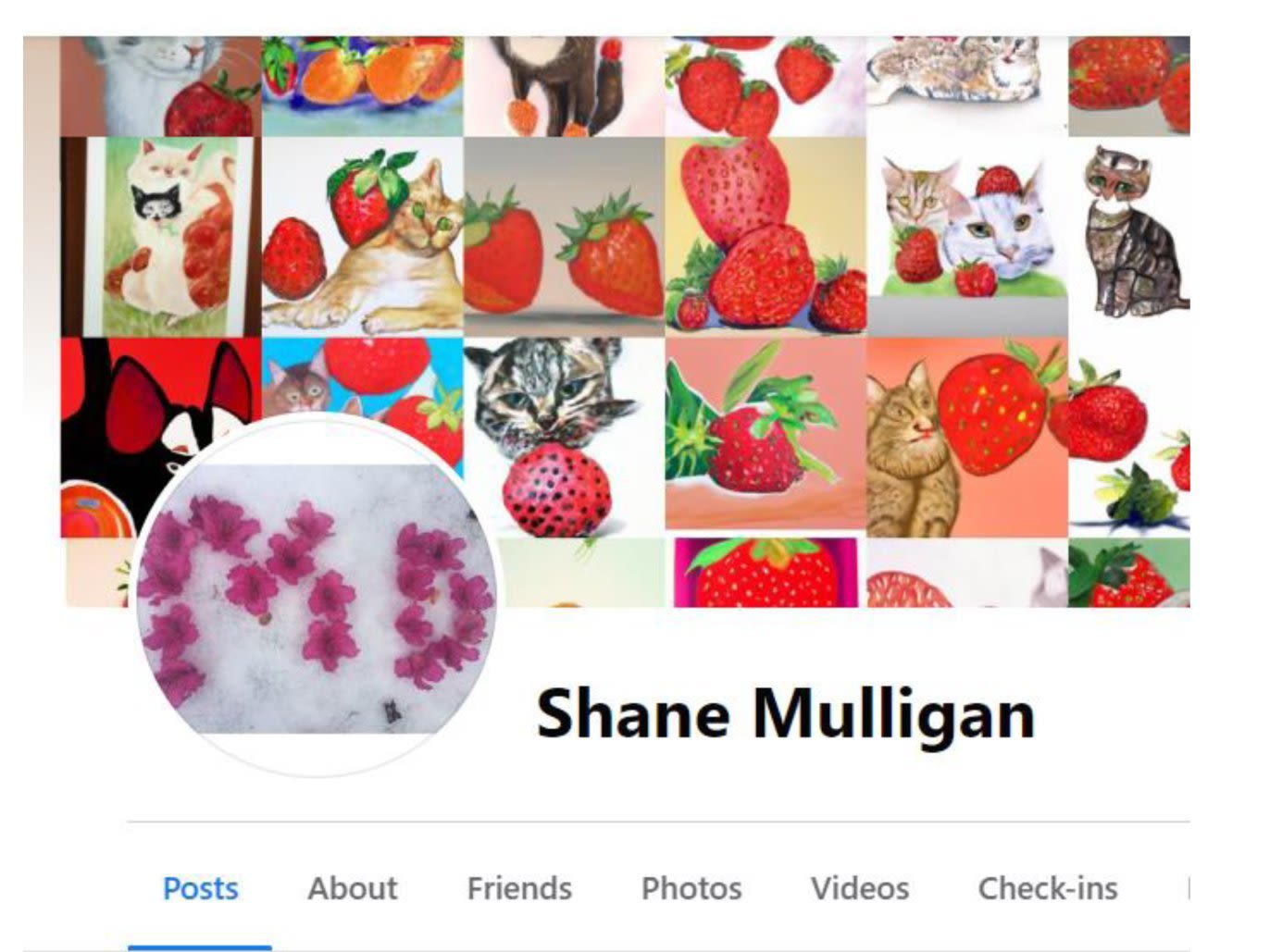

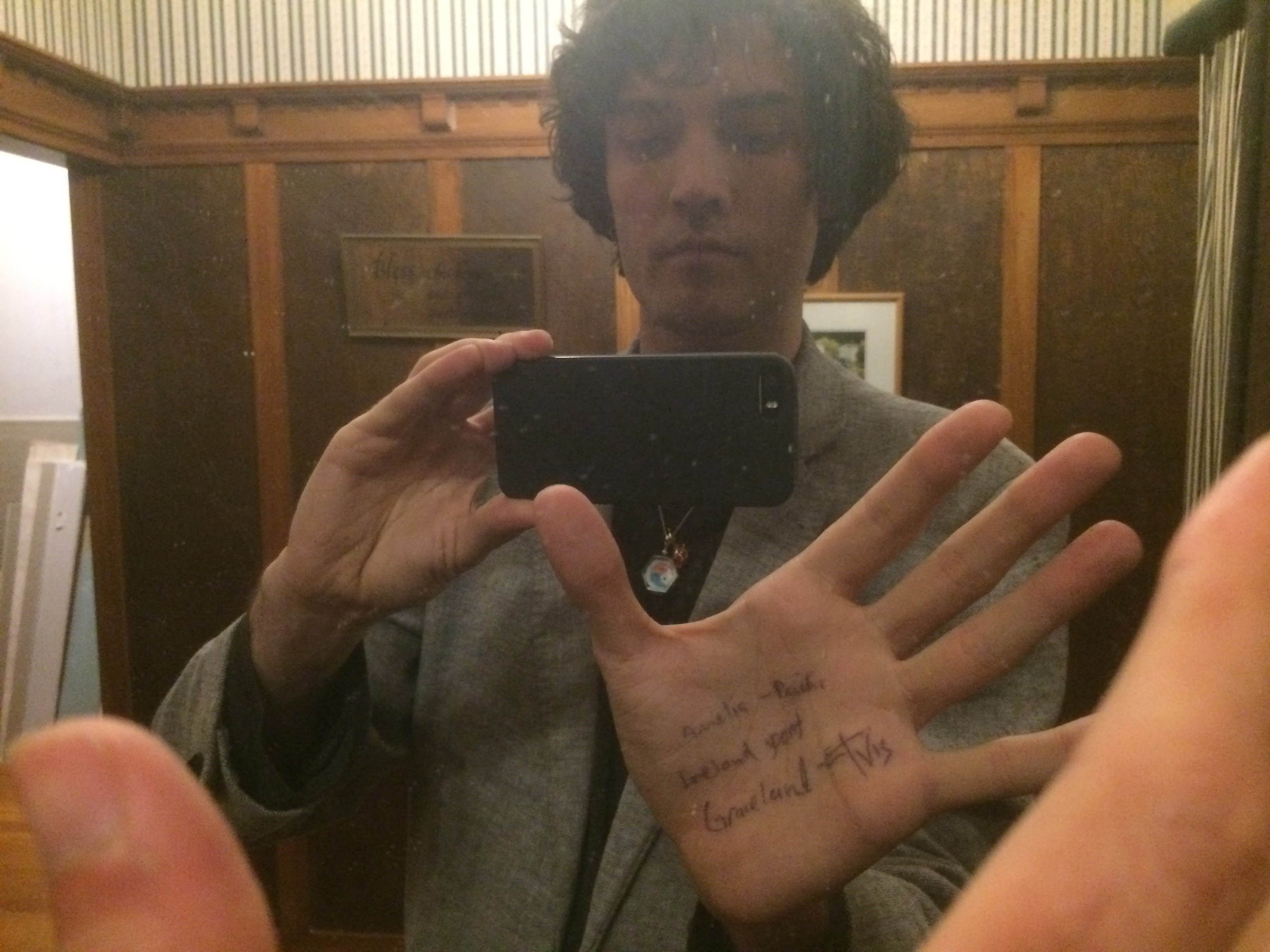

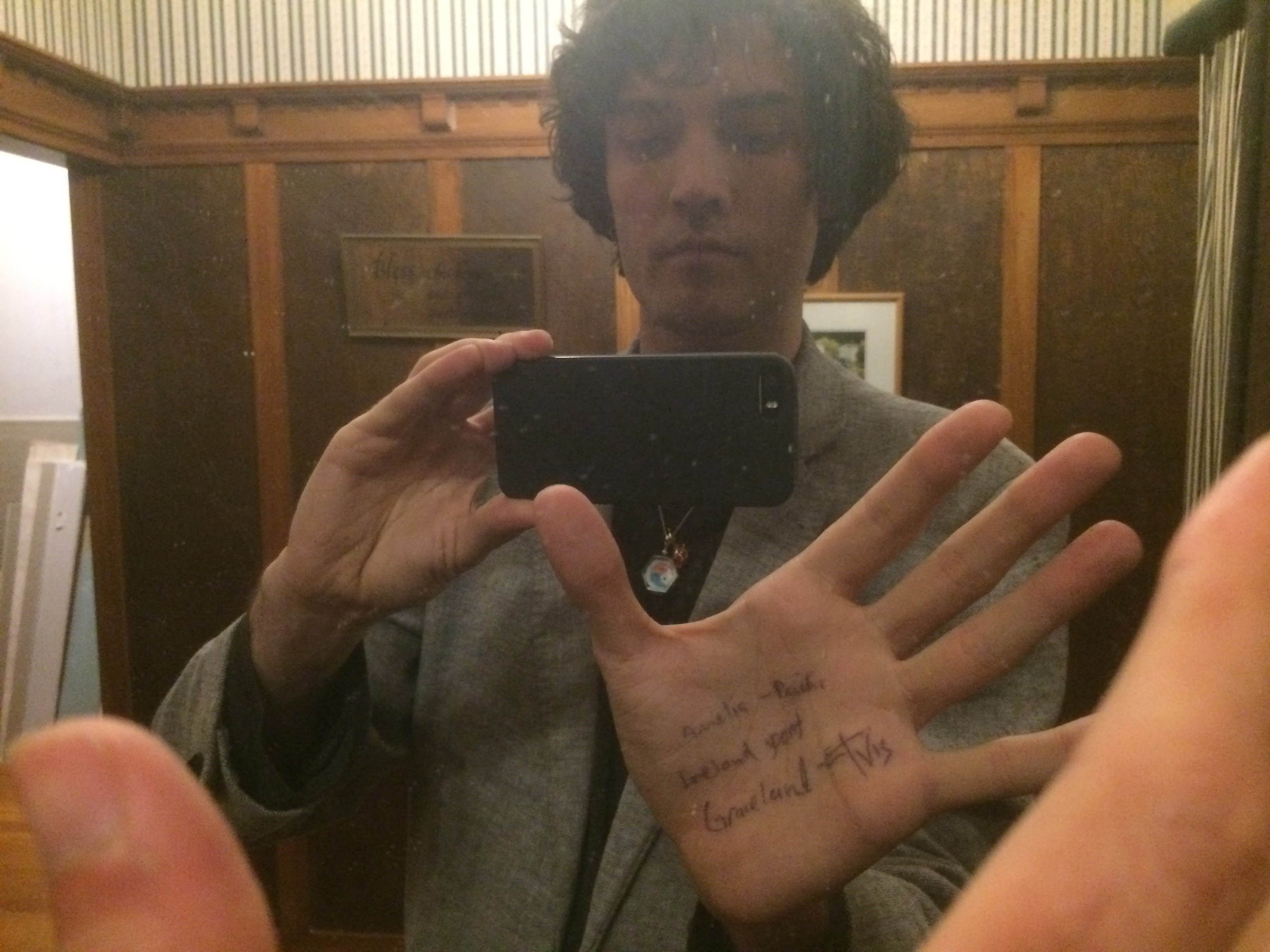

Sentenced . . . Shane Mulligan pleaded guilty to harassment and was sentenced to intensive supervision. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

Sentenced . . . Shane Mulligan pleaded guilty to harassment and was sentenced to intensive supervision. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

Ms Dowle had mentioned during her brief chat with Mulligan that she liked strawberries.

Starved of any information about the girl, he fixated on this minuscule detail and it became a theme of his online ramblings in the ensuing years.

Weeks after their first meeting, Mulligan messaged her while they were in church to meet him at the back of the building.

It was Valentine’s Day and he had strawberry brownies.

‘‘He painted it like he was handing them out to everyone but when I got there he was standing there with a box.

‘‘When I left, I realised . . . it was just me he was giving them to,’’ Ms Dowle said.

Meanwhile, the late-night messages that flooded her inbox while she slept were becoming less intelligible and more frequent.

Ms Dowle was staggered by the unrelenting intensity and did not know how to stop it.

She was embarrassed and, though she had done nothing to encourage Mulligan’s advances, she felt somehow responsible.

She blocked him on Facebook and her brother, who knew him through IT circles, warned him off.

And it appeared to work.

For a year, Ms Dowle resumed normal life: school, friends, plans for university.

‘‘I had moved on and forgotten,’’ she said.

Mulligan, though, was absorbed by his longing, only emboldened by the hurdles that had been put in his way.

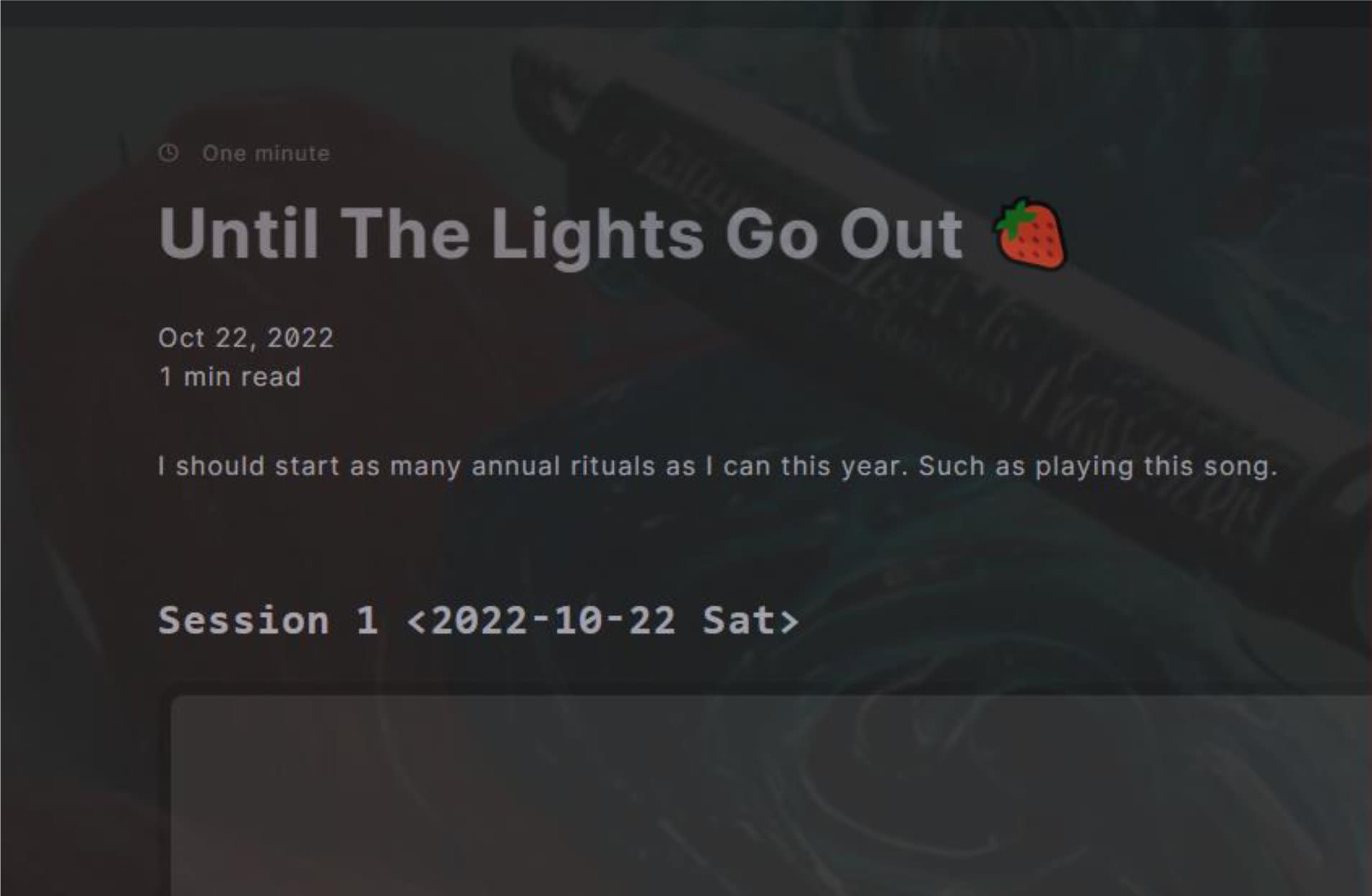

He poured his infatuation into his blog, a bizarre amalgamation of theology, artificial intelligence and art.

And at the centre of it, was Melee Dowle.

But what becomes increasingly obvious when trawling through the thousands of words that he wrote is that this person he ‘‘loved’’, with whom he was destined to spend eternity, his supposed soul’s reflection — he did not know her at all.

Strawberries, cats and art were the crumbs of Ms Dowle’s life he had gleaned from the limited contact they had shared, so Mulligan clung to them with desperate zeal.

‘‘He started obsessing over the little things I’d mentioned because that was all he really had,’’ she said.

‘‘I was extremely uncomfortable but I was also just horrified, because I didn’t realise it had gone to this extent.’’

In August last year, Ms Dowle was sent a link by one of Mulligan’s friends to a new online post.

It was entitled ‘‘Marry Me Melee’’ and featured 55 bullet points explaining and justifying why their union must happen.

It reads as simultaneously intricately penned and haphazardly spewed onto the page.

‘‘I have to find the infinity inside of Melee: That has to be my focus. That’s how she becomes my world, then the external reality becomes the playground. I will absolutely plaster my website with anything that Melee will give me. Asides from that I will love her to infinity,’’ Mulligan wrote.

The document was also wildly contradictory.

In one line, Mulligan wrote about waiting for her to approach him, then on the very next his impatience seemed to overwhelm him.

‘‘In my personal mythology, I think it’s actually essential that I marry Melee.’’

It was enough to push Ms Dowle to contact police and a week later Mulligan was served with a harassment order warning him that a continuation of his behaviour could result in a prosecution and up to two years’ imprisonment.

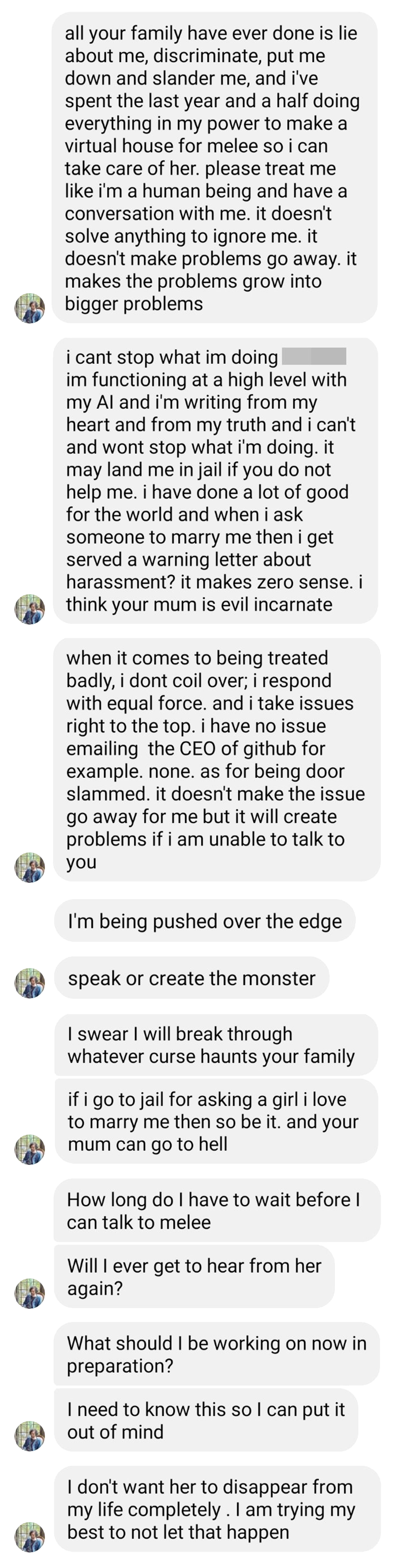

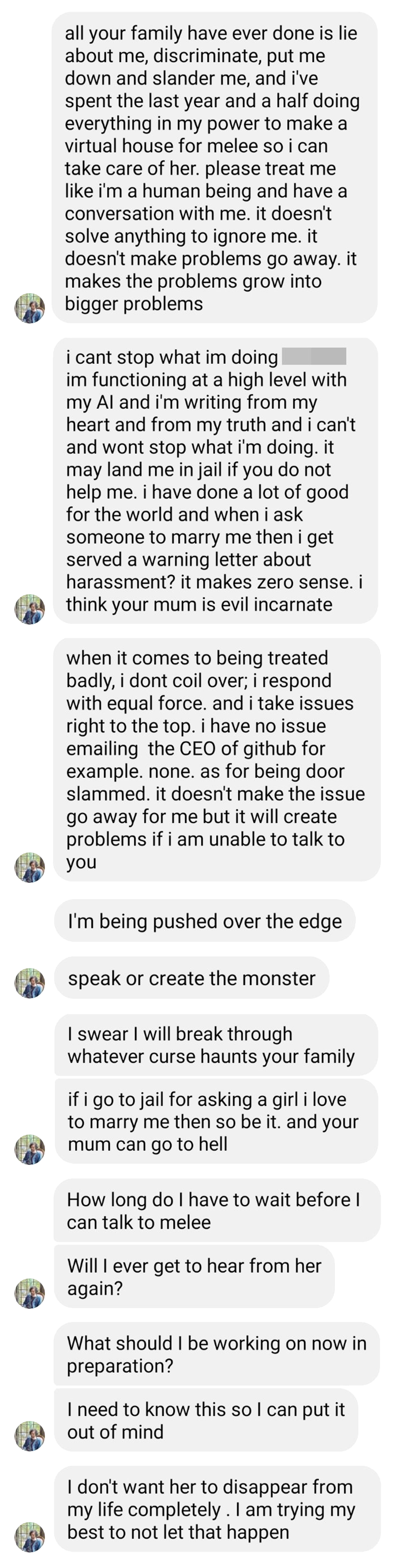

Within hours he had contravened the order, contacting the victim’s brother and explaining his warped philosophy.

‘‘I’ve spent the last year and a half doing everything in my power to make a virtual house for Melee so I can take care of her,’’ he wrote.

Over 18 hours, Mulligan sent 21 messages, becoming increasingly vehement about his need to speak to Ms Dowle.

‘‘When it comes to being treated badly, i dont coil over; i respond with equal force [sic],’’ Mulligan said.

And later: ‘‘I’m being pushed over the edge . . . speak or create the monster.’’

For the first time, the stalker had shown his teeth.

The tirade prompted police to lay charges, but heading towards the end of last year, it appeared they would be dealt with by diversion.

Mulligan would preserve his clean criminal record, he simply had to leave Ms Dowle alone.

But that hardship was evidently beyond him.

Through November, he continued to blog about the victim, tactlessly replacing her name with a strawberry icon.

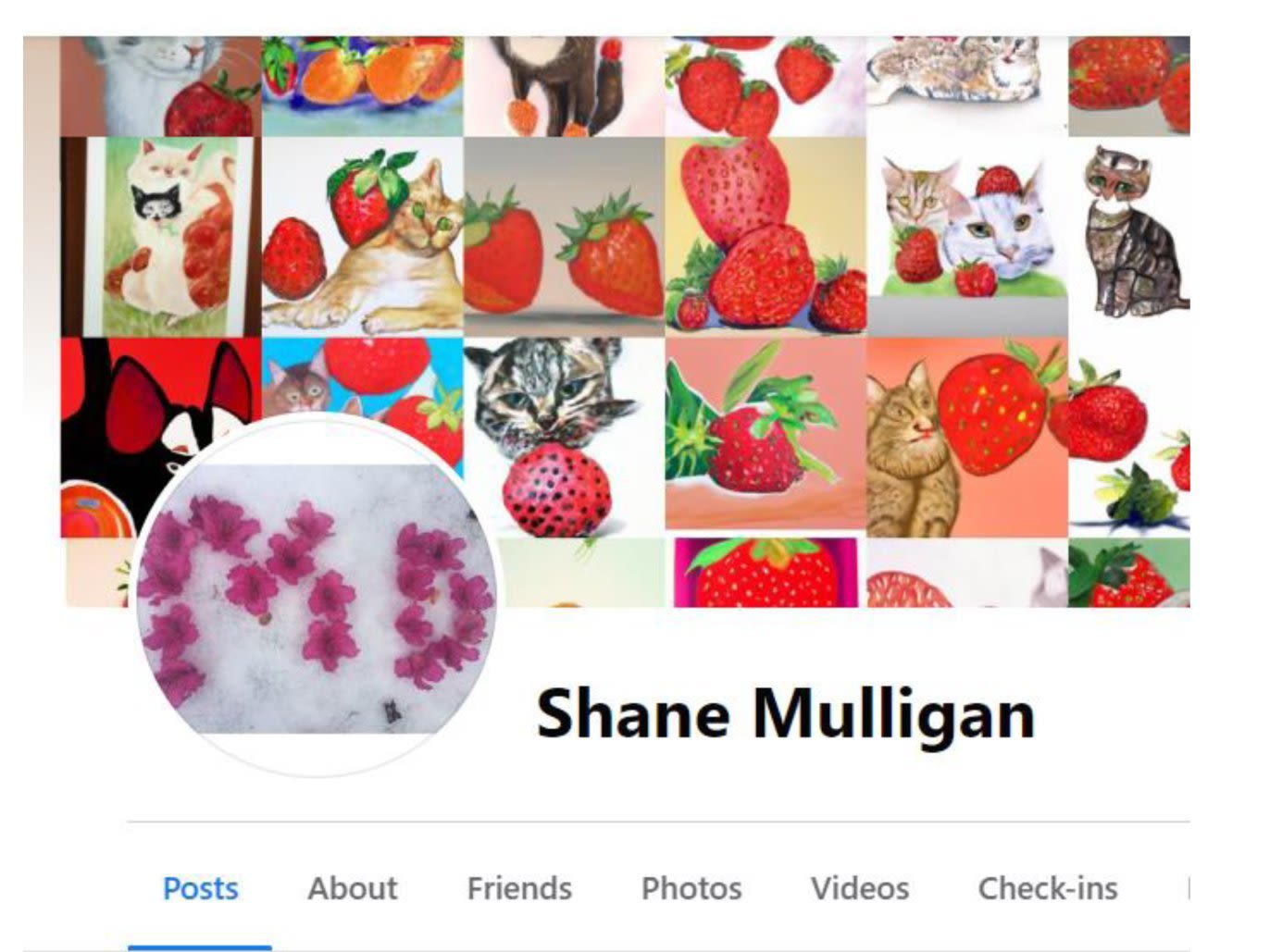

His Facebook profile photo became ‘‘MD’’ written in petals and there was the now predictable torrent of strawberry and cat images.

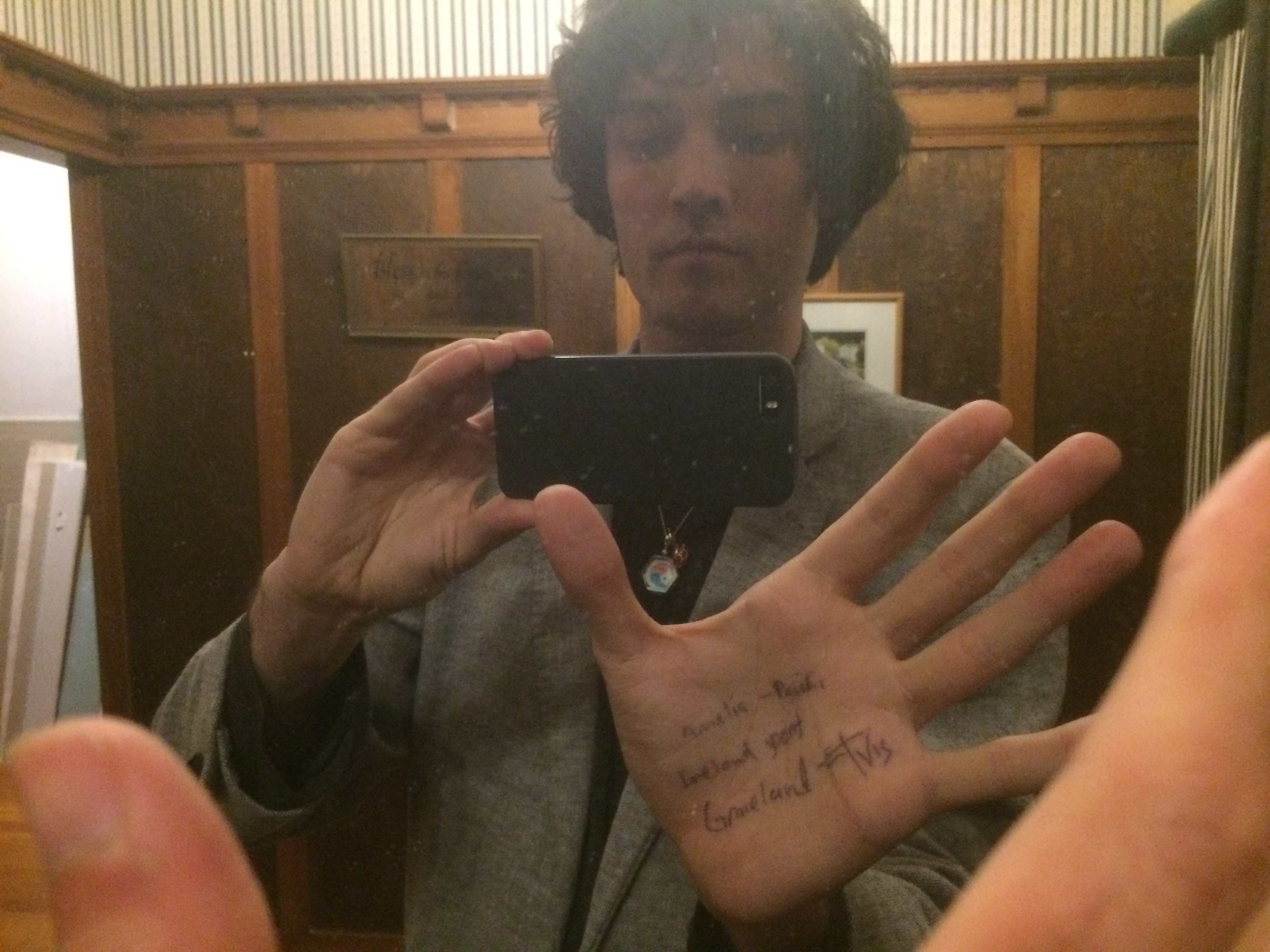

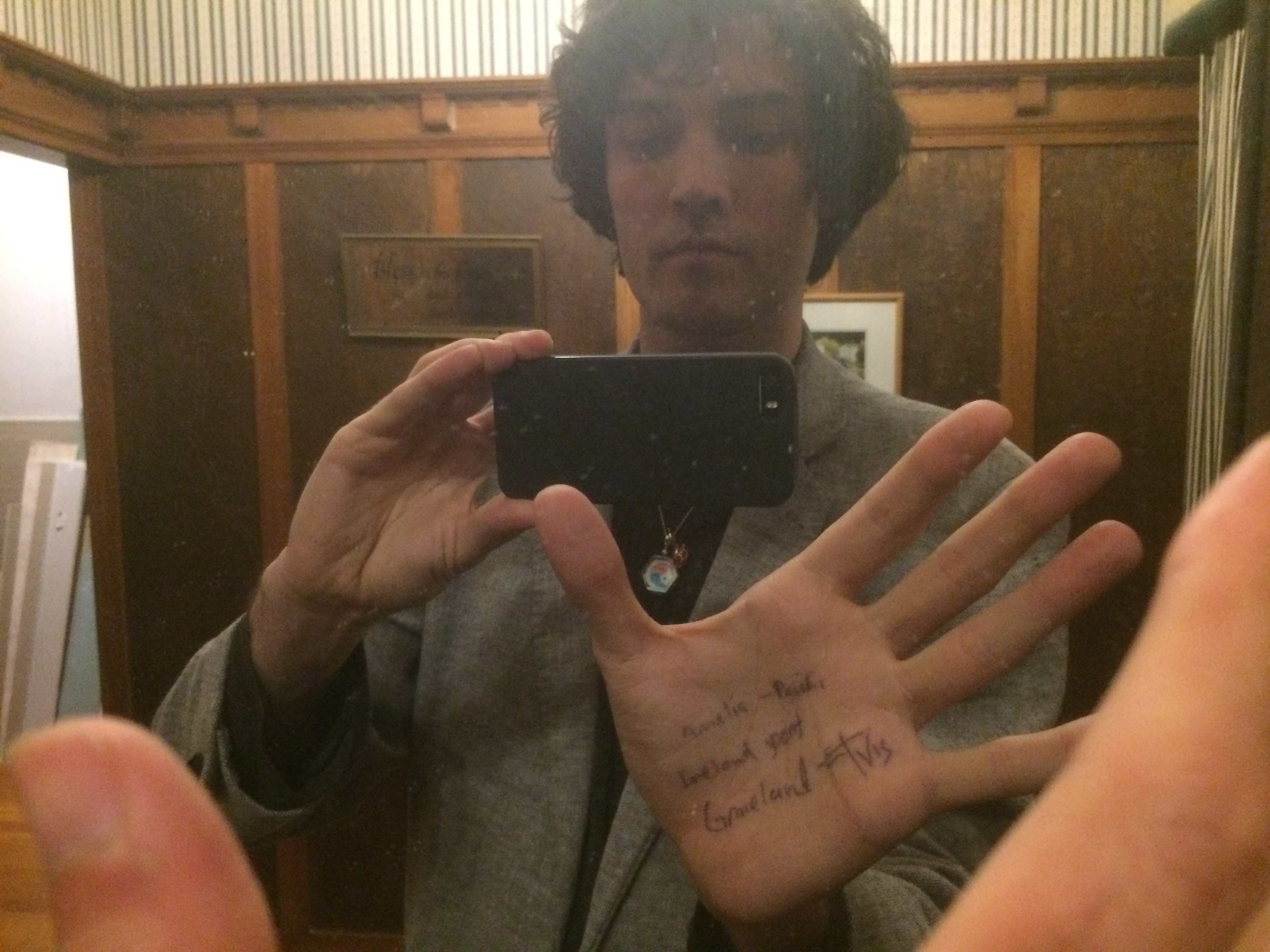

Mulligan posted a selfie with Ms Dowle’s full name written on his hand, trying to pass it off as coincidental answers in a quiz he had attended.

It was enough for police to withdraw the diversion offer and yet he was not done.

In January, Mulligan targeted Ms Dowle’s sister, subjecting her to an inane barrage of bible quotes and dream interpretation.

He flitted from ancient symbolism to football, from the poetry of Lewis Carroll to Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

‘‘She’s all I love in this world . . . please don’t call the police on me [prayer hands emoji],’’ Mulligan wrote.

More charges were laid.

Ms Dowle’s family had extra cause for outrage.

A woman — whom the ODT has agreed not to name — contacted them after hearing about the torture Mulligan was inflicting.

Years earlier, she had had a similar experience and she was shocked to hear it had happened again.

‘‘I remember getting these weird messages about marriage and him wanting to ‘watch me always’ too . . . When I was very brutal with him about never wanting him near my house again, he went back to endless messages until I blocked him,’’ she said.

Just as he had with Ms Dowle, Mulligan had professed his love and pressed on despite repeated rejections.

The woman did not think him capable of physical violence, but said his more recent behaviour seemed to be more fervid.

‘‘He becomes so caught up in his own beliefs and convictions that it seems like no-one can reach him, and any opposition to his thoughts gets treated as a ‘challenge’ to his higher purpose,’’ she said.

Clinical psychologist Anja Isaacson said it was a common theme with a stalker’s mindset: ‘‘The more you resist, the more I’m going to persist. The more obstacles you put in my way, I’m going to be the gallant knight to overcome all quests and you will see you can only love me’’.

It is a Hollywood movie trope that has existed for generations.

We are seduced into believing love conquers all — but it can only be when there is some foundation of reciprocity.

The context which most frequently led to stalking was the breakdown of an intimate relationship, but it was not rare for an unremarkable encounter to lead to relentless pursuit, Ms Isaacson said.

Typically such scenarios arose because of a person’s desire for intimacy, and though it usually began with a slow ‘‘grooming period’’, it could rapidly escalate.

‘‘Over time it could progress to something like possession,’’ Ms Isaacson said.

‘‘Possession almost serves to reduce the human being to something less than human. So they become an object of the person’s desire. They reside in the person’s fantasy and the victim has no will. It’s driven by this whole sense of wanting to control. And oftentimes, that can become more intrusive.’’

The impact for victims could be lifelong.

‘‘It’s a violation. When we close our doors and we go away, we feel violated if somebody’s come into our house and fiddled around in our drawers, and this is almost similar. You don’t feel that you have your privacy.

‘‘The saddest thing for victims is a stalker almost gets exactly what they want . . . [Victims are] required to change their daily schedule, reduce their online profile, change their name. They’re the ones who are supposed to do everything to almost become somebody else who’s now safe, because the them that is authentic is not safe. It’s so unfair,’’ she said.

After three years of words, it was his counsel Deborah Henderson who did the talking in court.

‘‘Today is a day people can move on,’’ she insisted.

While she emphasised Mulligan’s remorse, it did not wash with Judge Large, who focused on an unusual letter the man had penned to the court.

There was to be no grovelling apology.

‘‘I forgive the Dowle family and I have no grudge against them,’’ Mulligan wrote.

The judge attempted to set him straight.

‘‘It’s not for him to give forgiveness . . . he’s the one to have wronged others. I wonder if that message has hit home to him,’’ he said.

Ms Henderson suggested a sentence of community work; her client did not need rehabilitation since he already had ‘‘supports’’.

But that was rejected.

On the charge of harassment, Judge Large imposed 18 months’ intensive supervision, meaning Corrections could direct Mulligan to undertake any treatment deemed appropriate.

For Ms Dowle, the crucial element of the court process was a conviction, a censure which may prevent him from working with young women in future.

In an online exchange with the ODT, Mulligan said he had not yet been referred for any therapy and stressed he had no history of mental health issues.

Ms Isaacson said that was not uncommon — up to 60% of stalkers had no diagnosable condition.

Mulligan, though, wrote of prophetic dreams (one of which apparently foresaw the shooting of prominent Dunedin activist Jack Brazil), his ability to see patterns in dates and claimed involvement in the Johnny Depp-Amber Heard trial.

He asked for his love of Jesus to be publicised, but was unrepentant when it came to his actions against Ms Dowle.

‘‘I made a marriage proposal to a completely eligible bachelorette,’’ Mulligan said.

So would he move on? Did he see himself finding real love?

‘‘Hmmm. did Adam divorce Eve then look for another partner?

‘‘I feel like having to give up Melee was like giving up my first born child. honestly i dont know if theres anyone out there for me. it’s no longer what matters [sic],’’ he replied.

Ms Dowle remained concerned about Mulligan’s lack of remorse and his gross misapprehensions.

Ultimately, all she wanted was her life back.

‘‘I have had to deal with fear and anger and finally now I want justice, closure and an end to this.’’

rob.kidd@odt.co.nz