In Central Otago, a river’s health is being

weighed against the demands of irrigation.

Mary Williams investigates the complex, dry,

catchment of the Manuherikia river

— and the struggle to restore it.

In Central Otago, a river’s health is being weighed against the demands of irrigation. Mary Williams investigates the complex, dry, catchment of the Manuherikia river — and the struggle to restore it.

High up between hills, on the banks of the Manuherikia River in the northern reaches of Central Otago, sits the tiny town of Omakau. On a cold winter’s day with a hoar frost, its cosy cafe is a blessing. Four local grandmothers and firm friends, Ruth, Margaret, Rona and Monica sit in the warmth and chat.

When asked how many children, grandchildren and great grandchildren they have between them, they run out of fingers and the precise number proves elusive. It is a lot. They reminisce about summers in the 1960s, by the river with their families.

Locals Margaret Matheson, Rona Sinclair, Monica Flannery and Ruth Kilkelly chat about the old days at Omakau’s Muddy Creek Cafe. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

“We used to take picnics after lunch, with half a gallon of cordial and biscuits — they were wonderful times,” says Ruth Kilkelly, 82 and mother of seven. There used to be a rope swing, but the river in summer can be too low for that now. The women talk of “sludgy” water — but don’t want to talk about the whys and wherefores. They leave that to the younger folk who run things around here.

The plateau below the Hawkdun Range in Oteake Conservation Park,

where the Manuherikia starts its journey. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

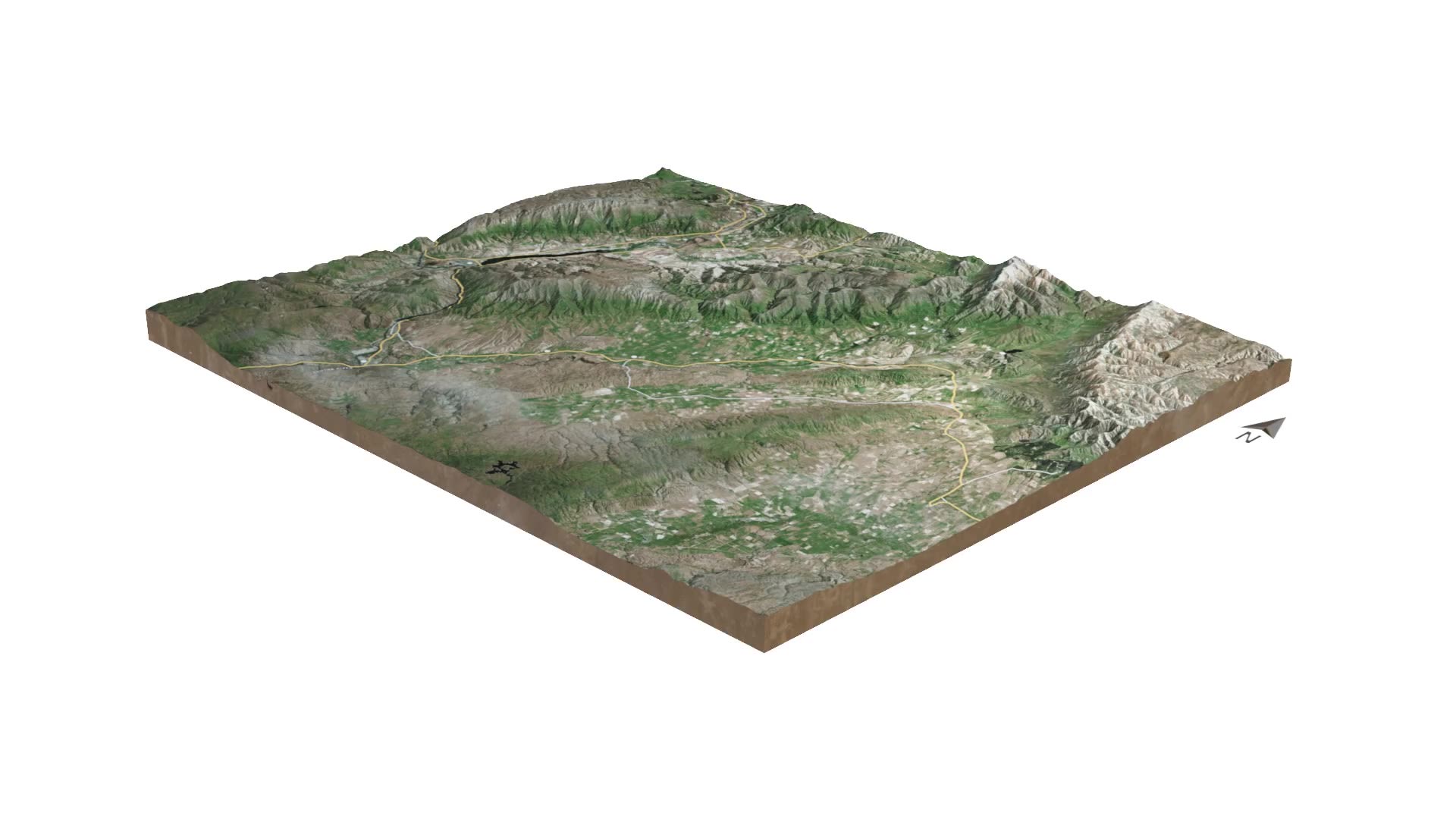

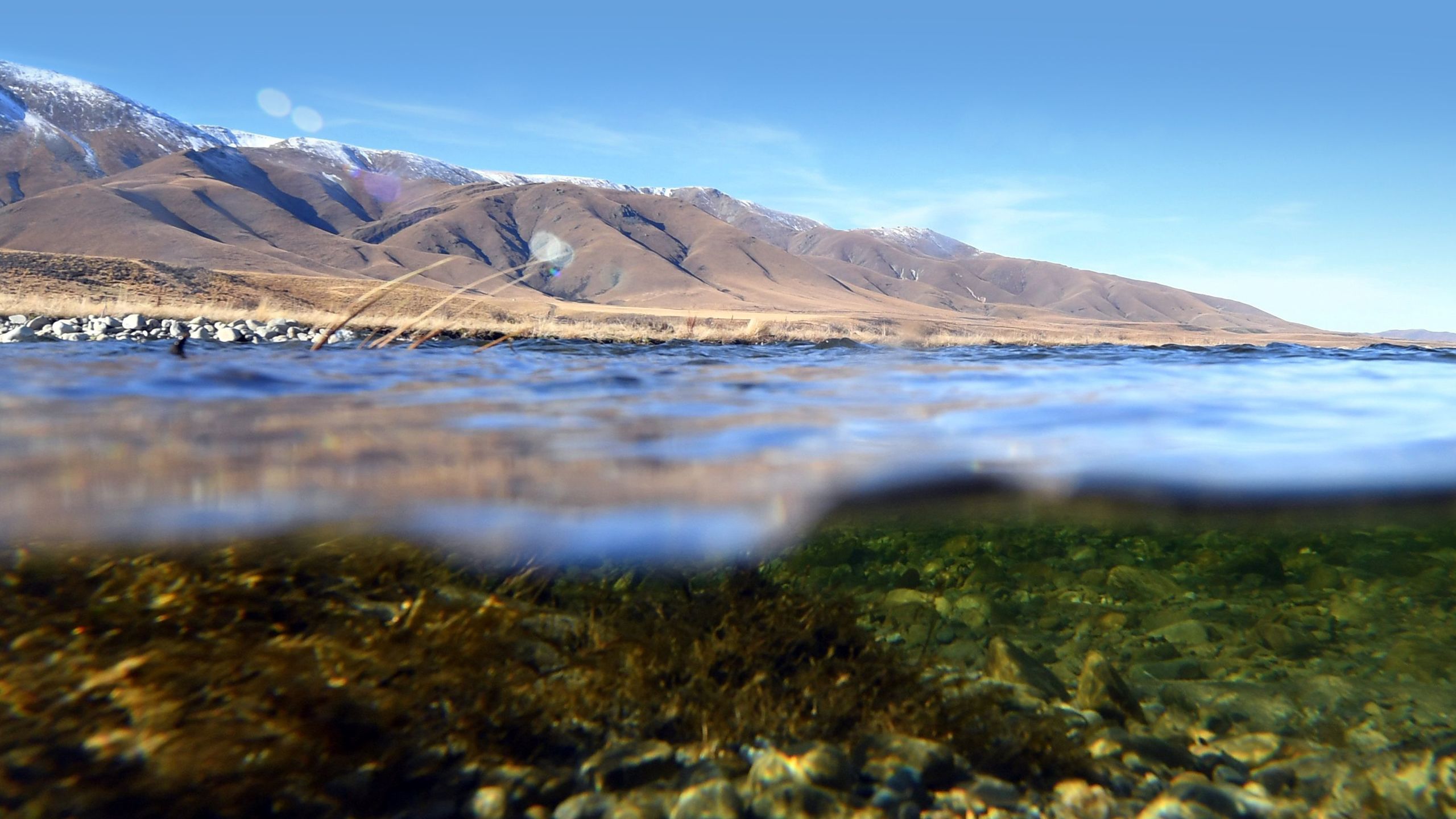

The Manuherikia River starts, like many rivers, spectacularly — in the hills of Oteake Conservation Park near the Canterbury border. It flows in wide braids across a high plateau, before descending to a catchment of two parallel valleys — the Manuherikia and Ida valleys.

Flowing past Omakau in the Manuherikia valley, it ends at Alexandra in the southwest, where it joins the Clutha river.

High up between hills, on the banks of the Manuherikia River in the northern reaches of Central Otago, sits the tiny town of Omakau. On a cold winter’s day with a hoar frost, its cosy cafe is a blessing. Four local grandmothers and firm friends, Ruth, Margaret, Rona and Monica sit in the warmth and chat.

When asked how many children, grandchildren and great grandchildren they have between them, they run out of fingers and the precise number proves elusive. It is a lot. They reminisce about summers in the 1960s, by the river with their families.

Locals Margaret Matheson, Rona Sinclair, Monica Flannery and Ruth Kilkelly chat about the old days at Omakau’s Muddy Creek Cafe.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

“We used to take picnics after lunch, with half a gallon of cordial and biscuits — they were wonderful times,” says Ruth Kilkelly, 82 and mother of seven. There used to be a rope swing, but the river in summer can be too low for that now. The women talk of “sludgy” water — but don’t want to talk about the whys and wherefores. They leave that to the younger folk who run things around here.

The Manuherikia River starts, like many rivers, spectacularly — in the hills of Oteake Conservation Park near the Canterbury border. It flows in wide braids across a high plateau, before descending to a catchment of two parallel valleys — the Manuherikia and Ida valleys.

Flowing past Omakau in the Manuherikia valley, it ends at Alexandra in the southwest, where it joins the Clutha river.

You can touch the soil,

lick your finger and

taste the salt

The river’s journey is through a unique, desert climate, with cold winters and hot summers. There is limited rainfall at the headwaters and less — about 400mm a year — in the valleys below. Moisture quickly evaporates.

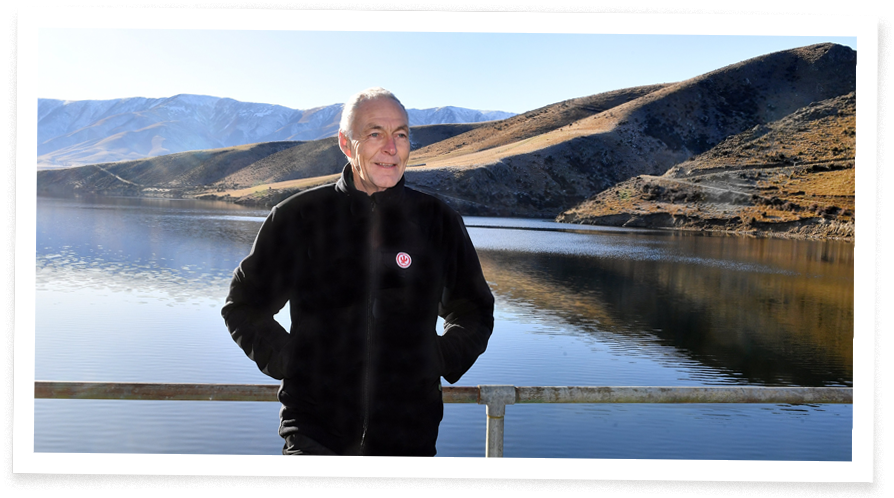

“You can touch the soil, lick your finger and taste the salt,” says Matt Sole, secretary of the Central Otago Environmental Society (COES).

Matt Sole, of the Central Otago Environmental Society, standing at the Manuherikia headwaters. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Once cloaked in diverse forest and shrubland with, surprisingly, some wetlands, this is still a special place with endangered species, explains Sole, including a rare tree daisy and the pārera — grey duck. The river is home to kōura — crayfish — and non-migratory galaxias, an ancient, scaleless fish.

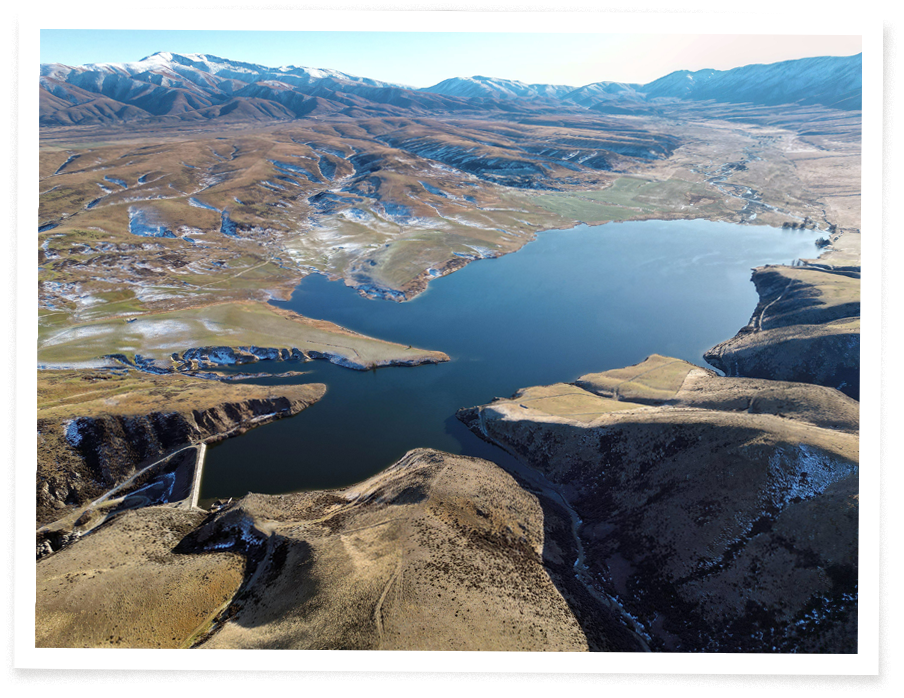

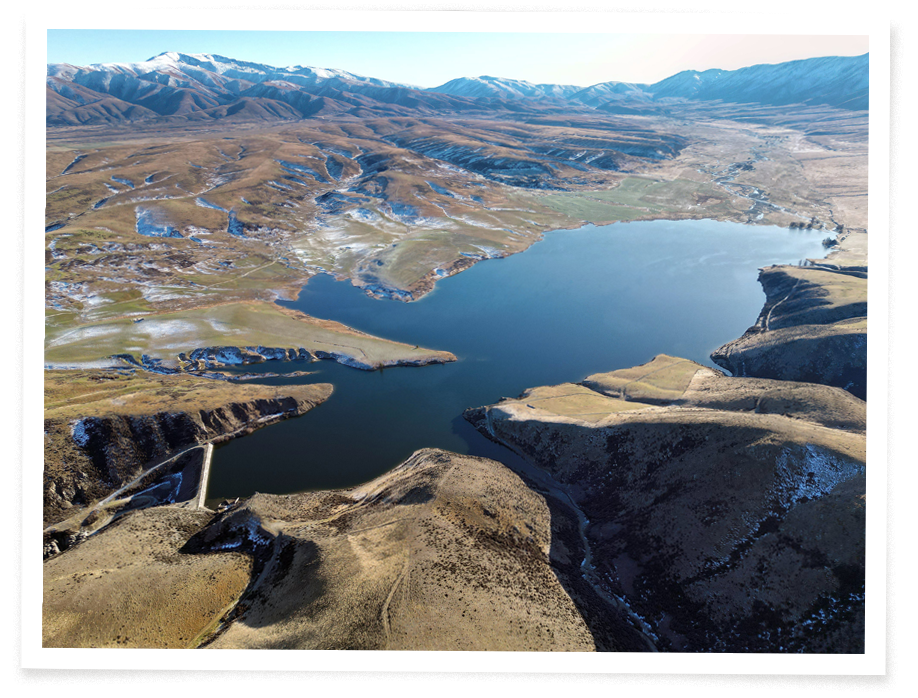

The river and its catchment, however, have a distinctly human modern history. Before entering the two valleys, the river is caught in a small dam — Falls Dam — built in the 1930s and nearing its life-expectancy. Water is then released below into a pretty gorge.

Falls Dam catches the Manuherikia headwaters then releases water — bottom left — into a gorge to continue the river’s journey south. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

The dam is one piece of a bigger, complex, jigsaw of irrigation infrastructure and irrigators, stretching across the catchment and dependent on the river and its many tributary creeks.

Across the Manuherikia and Ida valleys there are dams and races channelling water from the creeks and the river, mostly to irrigate grass and crops to feed animals. More than eight in 10 hectares in the 303,000ha catchment are used for livestock farming. Water storage ponds and bore holes also dot the landscape.

In summer, the river has least water to give, just when the valley’s irrigators are most dependent on it. Among them, are farmers who have invested significantly in modern irrigation equipment and farming business plans reliant on the continuation of permits allowing large water abstraction.

Farm irrigation in the Manuherikia and Ida valleys goes way back. In 1909, a government report supported water allocations to farmers to make “idle land” productive to “an incredible degree”. Farmers were demanding “give us water and the future is assured”. The farmers meant a future for their businesses and a community. They were granted huge water allocations, that had originally been used for gold mining. The irrigation infrastructure was built.

You can touch the soil, lick your finger and taste the salt

The river’s journey is through a unique, desert climate, with cold winters and hot summers. There is limited rainfall at the headwaters and less — about 400mm a year — in the valleys below. Moisture quickly evaporates.

“You can touch the soil, lick your finger and taste the salt,” says Matt Sole, secretary of the Central Otago Environmental Society (COES).

Matt Sole, of the Central Otago Environmental Society, standing at the Manuherikia headwaters.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Once cloaked in diverse forest and shrubland with, surprisingly, some wetlands, this is still a special place with endangered species, explains Sole, including a rare tree daisy and the pārera — grey duck. The river is home to kōura — crayfish — and non-migratory galaxias, an ancient, scaleless fish.

The river and its catchment, however, have a distinctly human modern history. Before entering the two valleys, the river is caught in a small dam — Falls Dam — built in the 1930s and nearing its life-expectancy. Water is then released below into a pretty gorge.

Falls Dam catches the Manuherikia headwaters then releases water — bottom left — into a gorge to continue the river’s journey south.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

The dam is one piece of a bigger, complex, jigsaw of irrigation infrastructure and irrigators, stretching across the catchment and dependent on the river and its many tributary creeks.

Across the Manuherikia and Ida valleys there are dams and races channelling water from the creeks and the river, mostly to irrigate grass and crops to feed animals. More than eight in 10 hectares in the 303,000ha catchment are used for livestock farming. Water storage ponds and bore holes also dot the landscape.

In summer, the river has least water to give, just when the valley’s irrigators are most dependent on it. Among them, are farmers who have invested significantly in modern irrigation equipment and farming business plans reliant on the continuation of permits allowing large water abstraction.

Farm irrigation in the Manuherikia and Ida valleys goes way back. In 1909, a government report supported water allocations to farmers to make “idle land” productive to “an incredible degree”. Farmers were demanding “give us water and the future is assured”. The farmers meant a future for their businesses and a community. They were granted huge water allocations, that had originally been used for gold mining. The irrigation infrastructure was built.

An irrigation gate and race takes water in the Manuherikia catchment. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

An irrigation gate and race takes water in the Manuherikia catchment. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Falls Dam was built in the 1930s depression by unskilled labourers. PHOTO: ODT FILES

Falls Dam was built in the 1930s depression by unskilled labourers. PHOTO: ODT FILES

Irrigated cattle grazing, fed by Manuherikia waters, marked by willows in the background. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Irrigated cattle grazing, fed by Manuherikia waters, marked by willows in the background. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Farming hasn’t stood still. An 1884 flour mill in the Ida Valley is now a converted home. Families farming sheep and beef cattle stayed for generations, irrigating. Omakau became a community and survived, despite the railway closing. The Otago Central cycle trail replaced the trains.

Sheep and beef cattle farming dominates here but dairy has taken a minority position, the first dairy platform established near Omakau in 2009. Dairy farmland increased more than 100-fold between 2008 and 2022 — from 20ha to 2241ha. Dairy support — grazing calves and cows for the dairy industry, including wintering of dairy herds, occupies another 3420ha.

There is agreement the dry climate is good for cows’ health. Pugging — wet pastures churned by cattle — is low risk. A dairy cow, however, can drink as much water as 30 lambs on a dry pasture. Beef cattle drink as much as 20 lambs. Irrigated cattle farming also means significant risk of river pollution due to fertiliser and faeces run-off.

One sheep farmer, not wanting to be named, says: “It’s a matter of profits. It costs more to shear my sheep than I get for wool. Dairy farmers have been buying adjacent paddocks for grazing — and will swallow up my land if I sell. I won’t comment on their practices.”

This is a fragile

environment. It requires

gentle farming. I farm

in a way that sits best with

my conscience. There are

others, like me, just

getting by on the

old methods

He adds: “This is a fragile environment. It requires gentle farming. I farm in a way that sits best with my conscience. There are others, like me, just getting by on the old methods.”

Despite the irrigation infrastructure, not every farmer here irrigates. Hamish Cameron’s 4000ha “dry” farm, near Falls Dam, gets a little more rain than the farms further down the valleys. He only uses the river to supply drinking troughs for his sheep and cattle. In the driest times, he runs fewer stock. It is traditional farming. “The old boys weren’t stupid,” he says.

Farming hasn’t stood still. An 1884 flour mill in the Ida Valley is now a converted home. Families farming sheep and beef cattle stayed for generations, irrigating. Omakau became a community and survived, despite the railway closing. The Otago Central cycle trail replaced the trains.

Sheep and beef cattle farming dominates here but dairy has taken a minority position, the first dairy platform established near Omakau in 2009. Dairy farmland increased more than 100-fold between 2008 and 2022 — from 20ha to 2241ha. Dairy support — grazing calves and cows for the dairy industry, including wintering of dairy herds, occupies another 3420ha.

There is agreement the dry climate is good for cows’ health. Pugging — wet pastures churned by cattle — is low risk. A dairy cow, however, can drink as much water as 30 lambs on a dry pasture. Beef cattle drink as much as 20 lambs. Irrigated cattle farming also means significant risk of river pollution due to fertiliser and faeces run-off.

One sheep farmer, not wanting to be named, says: “It’s a matter of profits. It costs more to shear my sheep than I get for wool. Dairy farmers have been buying adjacent paddocks for grazing — and will swallow up my land if I sell. I won’t comment on their practices.”

This is a fragile environment. It requires gentle farming. I farm in a way that sits best with my conscience. There are others, like me, just getting by on the old methods

He adds: “This is a fragile environment. It requires gentle farming. I farm in a way that sits best with my conscience. There are others, like me, just getting by on the old methods.”

Despite the irrigation infrastructure, not every farmer here irrigates. Hamish Cameron’s 4000ha “dry” farm, near Falls Dam, gets a little more rain than the farms further down the valleys. He only uses the river to supply drinking troughs for his sheep and cattle. In the driest times, he runs fewer stock. It is traditional farming. “The old boys weren’t stupid,” he says.

Hamish Cameron runs sheep and beef

on his “dry” farm near Falls Dam.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Below Cameron it is also possible to “dry” farm. In the Ida Valley, Barney Dundass has farmed sheep since 1962, without irrigation, on his 484 hectares at Moufeyvale farm. He dry-farms 3000 ewes and 600 hoggets. Lambs leave before they are six months, to limit water use.

The Ida Burn flows through his land. Only it doesn’t — in summer. It is “completely dry” for 5km, he says. His neighbours are irrigating farmers.

The creek

stops when the

irrigators start

“The creek stops when the irrigators start,” Dundass says, sounding factual, not furious. He thinks there would “probably still be water in the creek if there was no irrigation.”

Dundass gets by. “I would not like to be a young farmer trying to farm with irrigation, not with the cost of the new equipment.” He adds with a smile: “I’m quite happy the way I am — and too bloody old to change now anyway.”

Jillian Sullivan is an environmental writer living in the Ida Valley who talks about new methods. She says: “We need a society-wide approach — government and consumers — to help irrigating farmers transition to farming that doesn’t require so much water or fertilising. It can happen — there are opportunities.” She talks about drought-resistant crops.

Barney Dundass feeds baleage to merinos in the Ida Valley frost. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

In the driest times, at the river’s headwaters, only 0.5 cumecs — cubic metres per second — enters Falls Dam, says dam manager Roger Williams.

If there were no irrigation infrastructure, the river would get bigger as it flows down and creeks feed into it, even in these driest times. A “mean annual low flow” — the average lowest flow the river could expect to reach during the driest times — would naturally be about 4 cumecs in Alexandra, according to hydrologist advice given to Otago Regional Council (ORC). At other times, the river would usually be much higher.

Things are not natural at the moment. At Alexandra’s campground, the river flows as low as 0.9 cumecs during the driest times. At these times, its channels are narrow and ankle deep in places. It doesn’t dry up entirely only because the irrigators collaborate to ration their use at these times to head-off that outcome.

Hamish Cameron runs sheep and beef on his “dry” farm near Falls Dam.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Below Cameron it is also possible to “dry” farm. In the Ida Valley, Barney Dundass has farmed sheep since 1962, without irrigation, on his 484 hectares at Moufeyvale farm. He dry-farms 3000 ewes and 600 hoggets. Lambs leave before they are six months, to limit water use.

The Ida Burn flows through his land. Only it doesn’t — in summer. It is “completely dry” for 5km, he says. His neighbours are irrigating farmers.

The creek stops when

the irrigators start

“The creek stops when the irrigators start,” Dundass says, sounding factual, not furious. He thinks there would “probably still be water in the creek if there was no irrigation”.

Dundass gets by. “I would not like to be a young farmer trying to farm with irrigation, not with the cost of the new equipment.” He adds with a smile: “I’m quite happy the way I am — and too bloody old to change now anyway.”

Jillian Sullivan is an environmental writer living in the Ida Valley who talks about new methods. She says: “We need a society-wide approach — government and consumers — to help irrigating farmers transition to farming that doesn’t require so much water or fertilising. It can happen — there are opportunities.” She talks about drought-resistant crops.

Barney Dundass feeds baleage to merinos in the Ida Valley frost.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

In the driest times, at the river’s headwaters, only 0.5 cumecs — cubic metres per second — enters Falls Dam, says dam manager Roger Williams.

If there were no irrigation infrastructure, the river would get bigger as it flows down and creeks feed into it, even in these driest times. A “mean annual low flow” — the average lowest flow the river could expect to reach during the driest times — would naturally be about 4 cumecs in Alexandra, according to hydrologist advice given to Otago Regional Council (ORC). At other times, the river would usually be much higher.

Things are not natural at the moment. At Alexandra’s campground, the river flows as low as 0.9 cumecs during the driest times. At these times, its channels are narrow and ankle deep in places. It doesn’t dry up entirely only because the irrigators collaborate to ration their use at these times to head-off that outcome.

The river has been flipped by irrigation infrastructure abstraction — its flow reduces in summer months as it flows down from Falls Dam to Alexandra.

At an Alexandra swimming spot called Shaky Bridge, just below the campground, the ORC monitors water quality. Swimming after heavy rain is not recommended. The river’s long-term grade is poor. Bacterial sources are sheep, cow — and human too. Campground owner Janice Graham says: “It varies from good to brown. It oozes up through the gravel in places.”

She thinks there is farm run-off, adding, “This part of the country doesn’t lean to dairy”.

Further upstream there is a water health monitoring site at the small settlement of Ophir. Its results are publicised by Land Air Water Aotearoa (LAWA), a partnership of academics and government. LAWA describes poor water quality due to bywash and makes a direct link to irrigation “allowing higher intensity farming”, including wintering dairy herds and dairying platforms.

The Omakau waste water treatment plant also discharges into the river.

LAWA communication lead Nicole Taber says: “Armed with data, people can support informed decision-making — we have a right to know the state of rivers and the critters in them.”

The “critters” include benthic macroinvertebrates, ranging from insect larvae to the native crayfish. They have no backbones but are the backbone of the river’s ecosystem and food for fish and wading birds. When larvae turn into insects and leave the water they become food for other birds and bats.

Heavy sediment in the Manuherikia five days after rain. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

Heavy sediment in the Manuherikia five days after rain. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

Fish barrier in Thomsons Creek to protect Central Otago roundhead galaxias. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

Fish barrier in Thomsons Creek to protect Central Otago roundhead galaxias. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

The native Central Otago roundhead galaxiid — native fish reliant on clean water that flows. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

The native Central Otago roundhead galaxiid — native fish reliant on clean water that flows. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

LAWA grades river health indicators A to E, with E being poorest. At Ophir, the macroinvertebrate community is graded C and “very likely degrading”. The river is graded D for sediment, which can be caused by farmland run-off and algal bloom, and D for presence of E.coli, the harmful bacteria. Prior to 2010, it barely registered. Now, on about one in four days, the infection rate is high risk — about a 1 in 30 chance of infection.

Dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and phosphorous — common farm run-off pollutants — have also been detected at higher rates since 2010 and is “likely degrading”.

The overall picture is a river at risk.

The priorities of Te Mana o te Wai — the Government’s commitment to healthy freshwater — are as clear as Manuherikia headwaters. First, the health of the river. Second, water for people. Third, water for businesses. Te Mana o te Wai guides the Government’s policy statement for freshwater management, which in turn guides local councils’ water management plans. Rivers must be kept clean and polluted rivers cleaned up. Habitats of indigenous freshwater species must be protected.

Over-allocated rights to water use must be phased out.

At the same time as environmental policy is taking precedence nationally, the large water allocations given to Manuherikia irrigators have ended. The ORC has issued short-term permits while it finalises its long-term Land and Water Regional Plan (LWRP), expected to be notified by the end of June 2024.

Irrigating farmers have expressed concern about the short-term permits. They want long-term assurances of their businesses’ futures.

Feelings ran high at 2021 public meetings about Manuherikia water allocations.

PHOTO: SHANNON THOMSON

In 2021, an ORC plan for higher minimum flow levels was proposed, after a research and consultation exercise costing more than $3 million. The ORC proposed increasing a minimum flow level at Alexandra from 0.9 cumecs to 1.2 cumecs, then 2 cumecs in 2037 — and likely higher after that. The council described its plan as “robust” and was “confident” its recommendations could be supported in a “hearing or Environment Court situation”.

Vocal irrigators gave the plan the thumbs down, saying no more than 1.1 cumecs was acceptable to them.

Two years on, a Manuherikia “technical advisory group” (TAG), informed by scientists, but including irrigator and environmental interests, is still informing the council’s decision-making on flow limits and deadlines to achieve them — which will then be incorporated into the LWRP.

Anita Dawe, ORC general manager, policy and science, says the TAG’s work is “progressing”. Hydrology and ecology reports are being completed and the group will provide feedback on those reports.

Council staff will then make recommendations on flows. A briefing of ORC councillors will happen in August, ahead of a community session. A further public consultation will then take place, including finalising a list of environmental outcomes for the river.

Dawe says the council is legally obliged to ensure the limits and their deadlines are “consistent with Te Mana o te Wai”. She says, for all rivers, council decisions are made “without the lens of current extraction. Once a decision is made, the current allocation will be assessed to determine whether the river is overallocated and therefore requires a phasing out period or whether there is still allocation available”.

Prior to the council’s 2021 flow-limit proposal, there had been many time-consuming debates, over years, about Manuherikia flow levels, including in a group convened by the ORC — the Manuherikia Reference Group (MRG). This group included people with irrigating interests and also environment-focused organisations such as COES, Forest & Bird and Fish & Game.

The group was meant to set “an intergenerational vision for managing water” and work towards it. However, although efforts were made to work together, positions polarised into views expressed as numbers.

Members with irrigating farm interests supported the view that a cumec flow at Alexandra at the driest times shouldn’t need to be raised much above its current 0.9 cumecs. Conversely, COES, Forest & Bird, Fish & Game and Kāi Tahu all expressed environmental concern and recommended that the council work towards a minimum flow at Alexandra much closer to the estimated natural average low flow. Kāi Tahu, for example, recommended up to 3.1 cumecs.

ORC councillors at the time had equally polarised positions. There was political disarray. Councillor Marian Hobbs, a former environment minister in Helen Clark’s government, eventually resigned from the council after being ousted from the chairperson role.

LAWA grades river health indicators A to E, with E being poorest. At Ophir, the macroinvertebrate community is graded C and “very likely degrading”. The river is graded D for sediment, which can be caused by farmland run-off and algal bloom, and D for presence of E.coli, the harmful bacteria. Prior to 2010, it barely registered. Now, on about one in four days, the infection rate is high risk — about a 1 in 30 chance of infection.

Dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and phosphorous — common farm run-off pollutants — have also been detected at higher rates since 2010 and is “likely degrading”.

The overall picture is a river at risk.

The priorities of Te Mana o te Wai — the Government’s commitment to healthy freshwater — are as clear as Manuherikia headwaters. First, the health of the river. Second, water for people. Third, water for businesses. Te Mana o te Wai guides the Government’s policy statement for freshwater management, which in turn guides local councils’ water management plans. Rivers must be kept clean and polluted rivers cleaned up. Habitats of indigenous freshwater species must be protected.

Over-allocated rights to water use must be phased out.

At the same time as environmental policy is taking precedence nationally, the large water allocations given to Manuherikia irrigators have ended. The ORC has issued short-term permits while it finalises its long-term Land and Water Regional Plan (LWRP), expected to be notified by the end of June 2024.

Irrigating farmers have expressed concern about the short-term permits. They want long-term assurances of their businesses’ futures.

Feelings ran high at 2021 public meetings about Manuherikia water allocations.

PHOTO: SHANNON THOMSON

In 2021, an ORC plan for higher minimum flow levels was proposed, after a research and consultation exercise costing more than $3 million. The ORC proposed increasing a minimum flow level at Alexandra from 0.9 cumecs to 1.2 cumecs, then 2 cumecs in 2037 — and likely higher after that. The council described its plan as “robust” and was “confident” its recommendations could be supported in a “hearing or Environment Court situation”.

Vocal irrigators gave the plan the thumbs down, saying no more than 1.1 cumecs was acceptable to them.

Two years on, a Manuherikia “technical advisory group” (TAG), informed by scientists, but including irrigator and environmental interests, is still informing the council’s decision-making on flow limits and deadlines to achieve them — which will then be incorporated into the LWRP.

Anita Dawe, ORC general manager, policy and science, says the TAG’s work is “progressing”. Hydrology and ecology reports are being completed and the group will provide feedback on those reports.

Council staff will then make recommendations on flows. A briefing of ORC councillors will happen in August, ahead of a community session. A further public consultation will then take place, including finalising a list of environmental outcomes for the river.

Dawe says the council is legally obliged to ensure the limits and their deadlines are “consistent with Te Mana o te Wai”. She says, for all rivers, council decisions are made “without the lens of current extraction. Once a decision is made, the current allocation will be assessed to determine whether the river is overallocated and therefore requires a phasing out period or whether there is still allocation available”.

Prior to the council’s 2021 flow-limit proposal, there had been many time-consuming debates, over years, about Manuherikia flow levels, including in a group convened by the ORC — the Manuherikia Reference Group (MRG). This group included people with irrigating interests and also environment-focused organisations such as COES, Forest & Bird and Fish & Game.

The group was meant to set “an intergenerational vision for managing water” and work towards it. However, although efforts were made to work together, positions polarised into views expressed as numbers.

Members with irrigating farm interests supported the view that a cumec flow at Alexandra at the driest times shouldn’t need to be raised much above its current 0.9 cumecs. Conversely, COES, Forest & Bird, Fish & Game and Kāi Tahu all expressed environmental concern and recommended that the council work towards a minimum flow at Alexandra much closer to the estimated natural average low flow. Kāi Tahu, for example, recommended up to 3.1 cumecs.

ORC councillors at the time had equally polarised positions. There was political disarray. Councillor Marian Hobbs, a former environment minister in Helen Clark’s government, eventually resigned from the council after being ousted from the chairperson role.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

A Kāi Tahu presentation to the MRG in 2019 stated that whānau with long association with the Manuherikia river knew a river with a greater flow and strong current. More recently than 2005, whānau had experienced a reduction in habitat and water deterioration, affecting access.

The MRG was eventually disbanded. Some ORC councillors continue to hold polarised positions but are required to work towards Te Mana o te Wai.

John Hayes is a freshwater ecology researcher who has advised the council. He says the hydrology is “challengingly complex” due to the irrigation systems but is confident that, without the irrigation, the estimated natural average low flow of 4 cumecs at Alexandra is “about right”. Below 3 cumecs there is an increasingly adverse impact risk on the critters in the river. “The risk can increase quite steeply the lower you go. It is turning the tap down on a river’s life force.” The number of days a river stays low also increases the risks, he adds.

Shallower and narrower river channels, due to low flow, reduces instream habitat — space — for invertebrates. It diminishes their feeding ground of periphyton. Periphyton is the natural “slime” on the bed of rivers that supports a complex community of algae, bacteria, fungi and invertebrates.

Reducing a river’s flow rate — its movement as well as its space — reduces the river’s natural flushing of sediment and invertebrates. Low and slow flow can cause damaging algal bloom.

“Think of a river like a farm,” Hayes says. “Taking flow out of it decreases its productivity. Would a farmer be happy to reduce their paddock size significantly? No. There is nothing clearer than an aerial photo showing bright green paddocks with a very dry river channel running between them. Increasing the productivity of farms decreases the productivity of a river.”

(Left) Stagnating pools in Thomsons Creek succumbing to water weed infestation.

(Right) Cropping for cattle in the Manuherikia catchment.

PHOTOS: SUPPLIED, STEPHEN JAQUIERY

The irrigating farmers who objected to the council’s 2021 plan for higher minimum flow levels include families who have farmed for generations. The river is no different to how their grandparents remembered it, maybe better, they say. The fishing can be good, too, they add.

Hayes says: “Unfortunately, because irrigation has gone on so long, some people can have a norm in their minds about what is natural for the level of the water — and the quality of the angling. It isn’t normal.”

A place that was attractive for cattle farming is now a place of fear and investment risk, particularly for farmers who have invested most, or bought farms valued on water rights. They have most to lose. Nobody knows the long-term allocations that will be granted nor the minimum flow levels that will be required by the council.

In a submission in 2021 objecting to short-term water allocations, Jan Manson, of Kye Farming, said her 550ha dairy farm had spent $3 million on “hard infrastructure” including pivot irrigation, dam storage and “precision fertiliser application and application of effluent back to the land”. With reference to her $1.9 million operating budget “rippling out” to the community, she described short-term water permits as “effectively slaughtering the goose regardless of its egg-laying capability”.

Environmentalist Matt Sole says she is describing a trap, into which others have also fallen.

“The farmers reliant on modern irrigating methods have become trapped in a business model at risk. The banks that lend to them are also not concerned about the environmental consequences. It’s like being given a car without a fuel gauge.”

The “wet” farms using spray irrigation operate with strategic efficiency. Their systems pivot and travel across paddocks, lightly spraying the top section of the soil when and where it is needed. Rather than seeping deep into the soil and returning to the catchment, water can be lost to evaporation. There is also the risk of the “efficiency paradox” — more land being converted from native tussock to monoculture paddock.

The irrigating farmers use several arguments to support their call for continued large water allocations. As well as wanting more hydrology evidence that higher levels are required for the river’s health, they are proud, not ashamed, of the 0.9 cumec lowest flow rate, achieved through their collaboration and irrigation efficiencies. They leave significant land “dry”. They don’t irrigate when there is rain. They irrigate “conservatively” and ration irrigation every few years when it gets particularly dry. The river is not dead or dying — it just has “pressure points” that can be “improved”.

They also argue they speak for the whole community because everyone uses Manuherikia water, including the small populations of Omakau, and Naseby in the east. They argue that horticulture, for example — including orchards — uses water too. About 500ha are used for commercial horticulture.

The Manuherikia Catchment Group (MCG) describes itself as a group of residents with a vision to use water “in a sustainable and co-operative way”. A deeper dive into MCG’s incorporation rules, however, explains its purpose is to “promote, support and advocate for the ongoing right to abstract water from the Manuherikia catchment”. Its committee is stocked with irrigating farmers who fund reports, and speak up, in favour of water allocations.

MCG members flag their involvement in environmental projects, including around Thomsons Creek near Omakau. This includes constructing a wetland, riparian planting and a barrier to protect galaxias from predation by trout and perch.

These efforts, however, have been significantly enabled by a cash injection from the Ministry for the Environment (MfE), specifically for “at risk catchments”.

ORC staffer Dawe supports “the good work that the rural sector has done as custodians of the environment”. However, Christine Rose, Greenpeace lead agriculture campaigner, begs to differ. “MfE funding for initiatives like the Thomsons Creek project is socialising the costs of environmental damage without addressing the main problem. Water extraction and nutrient enrichment, from industrial dairy in particular, threatens habitats,” she says.

“Particularly in the Manuherikia catchment, vested interests have sought to retain privileges which are sucking the life of the river dry. We are in a climate and biodiversity crisis and have a short time to restore the balance, and that means health of rivers must come first.”

Mary Flannery is on the MCG committee, a local lawyer and owner of a farm in the Ida Valley that she leases out. It was sheep and beef and is now dairy grazing. Flannery did a stint as a board member of Irrigation New Zealand (INZ), the organisation for irrigating farmers. She is adamant she doesn’t want her views described as “irrigator” views — she says she speaks for the community.

Manuherikia Catchment Group member Mary Flannery.

PHOTO: SUPPLIED

Without irrigation staying the same “we might have deeper water left in the river at Alexandra but if there is not a community, what would be the good of that? We need a good standard of living for everyone, which requires a good income.”

Sole says the MCG does not speak for him, nor other members of environment group COES. COES members are “shell shocked and battle weary” from trying to explain environmental imperatives to irrigators, he says.

“Portraying the community as united is a game the irrigators play — it is hard for people in a small community to speak out against the ‘farming firm’ here. But everyone contributes to society, not just farmers — including people outside these valleys who care about climate emergency and biodiversity. This is an issue of over-abstraction of water, degraded water quality, and land cover changes.”

When the ORC consulted people outside the valleys, there were more people wanting higher flows — and concerns about dairying and large water takes.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

A Kāi Tahu presentation to the MRG in 2019 stated that whānau with long association with the Manuherikia river knew a river with a greater flow and strong current. More recently than 2005, whānau had experienced a reduction in habitat and water deterioration, affecting access.

The MRG was eventually disbanded. Some ORC councillors continue to hold polarised positions but are required to work towards Te Mana o te Wai.

John Hayes is a freshwater ecology researcher who has advised the council. He says the hydrology is “challengingly complex” due to the irrigation systems but is confident that, without the irrigation, the estimated natural average low flow of 4 cumecs at Alexandra is “about right”. Below 3 cumecs there is an increasingly adverse impact risk on the critters in the river. “The risk can increase quite steeply the lower you go. It is turning the tap down on a river’s life force.” The number of days a river stays low also increases the risks, he adds.

Shallower and narrower river channels, due to low flow, reduces instream habitat — space — for invertebrates. It diminishes their feeding ground of periphyton. Periphyton is the natural “slime” on the bed of rivers that supports a complex community of algae, bacteria, fungi and invertebrates.

Reducing a river’s flow rate — its movement as well as its space — reduces the river’s natural flushing of sediment and invertebrates. Low and slow flow can cause damaging algal bloom.

“Think of a river like a farm,” Hayes says. “Taking flow out of it decreases its productivity. Would a farmer be happy to reduce their paddock size significantly? No. There is nothing clearer than an aerial photo showing bright green paddocks with a very dry river channel running between them. Increasing the productivity of farms decreases the productivity of a river.”

(Left) Stagnating pools in Thomsons Creek succumbing to water weed infestation. (Right) Cropping for cattle in the Manuherikia catchment. PHOTOS: SUPPLIED, STEPHEN JAQUIERY

The irrigating farmers who objected to the council’s 2021 plan for higher minimum flow levels include families who have farmed for generations. The river is no different to how their grandparents remembered it, maybe better, they say. The fishing can be good, too, they add.

Hayes says: “Unfortunately, because irrigation has gone on so long, some people can have a norm in their minds about what is natural for the level of the water — and the quality of the angling. It isn’t normal.”

A place that was attractive for cattle farming is now a place of fear and investment risk, particularly for farmers who have invested most, or bought farms valued on water rights. They have most to lose. Nobody knows the long-term allocations that will be granted nor the minimum flow levels that will be required by the council.

In a submission in 2021 objecting to short-term water allocations, Jan Manson, of Kye Farming, said her 550ha dairy farm had spent $3 million on “hard infrastructure” including pivot irrigation, dam storage and “precision fertiliser application and application of effluent back to the land”. With reference to her $1.9 million operating budget “rippling out” to the community, she described short-term water permits as “effectively slaughtering the goose regardless of its egg-laying capability”.

Environmentalist Matt Sole says she is describing a trap, into which others have also fallen.

“The farmers reliant on modern irrigating methods have become trapped in a business model at risk. The banks that lend to them are also not concerned about the environmental consequences. It’s like being given a car without a fuel gauge.”

The “wet” farms using spray irrigation operate with strategic efficiency. Their systems pivot and travel across paddocks, lightly spraying the top section of the soil when and where it is needed. Rather than seeping deep into the soil and returning to the catchment, water can be lost to evaporation. There is also the risk of the “efficiency paradox” — more land being converted from native tussock to monoculture paddock.

The irrigating farmers use several arguments to support their call for continued large water allocations. As well as wanting more hydrology evidence that higher levels are required for the river’s health, they are proud, not ashamed, of the 0.9 cumec lowest flow rate, achieved through their collaboration and irrigation efficiencies. They leave significant land “dry”. They don’t irrigate when there is rain. They irrigate “conservatively” and ration irrigation every few years when it gets particularly dry. The river is not dead or dying — it just has “pressure points” that can be “improved”.

They also argue they speak for the whole community because everyone uses Manuherikia water, including the small populations of Omakau, and Naseby in the east. They argue that horticulture, for example — including orchards — uses water too. About 500ha are used for commercial horticulture.

The Manuherikia Catchment Group (MCG) describes itself as a group of residents with a vision to use water “in a sustainable and co-operative way”. A deeper dive into MCG’s incorporation rules, however, explains its purpose is to “promote, support and advocate for the ongoing right to abstract water from the Manuherikia catchment”. Its committee is stocked with irrigating farmers who fund reports, and speak up, in favour of water allocations.

MCG members flag their involvement in environmental projects, including around Thomsons Creek near Omakau. This includes constructing a wetland, riparian planting and a barrier to protect galaxias from predation by trout and perch.

These efforts, however, have been significantly enabled by a cash injection from the Ministry for the Environment (MfE), specifically for “at risk catchments”.

ORC staffer Dawe supports “the good work that the rural sector has done as custodians of the environment”. However, Christine Rose, Greenpeace lead agriculture campaigner, begs to differ. “MfE funding for initiatives like the Thomsons Creek project is socialising the costs of environmental damage without addressing the main problem. Water extraction and nutrient enrichment, from industrial dairy in particular, threatens habitats,” she says.

“Particularly in the Manuherikia catchment, vested interests have sought to retain privileges which are sucking the life of the river dry. We are in a climate and biodiversity crisis and have a short time to restore the balance, and that means health of rivers must come first.”

Mary Flannery is on the MCG committee, a local lawyer and owner of a farm in the Ida Valley that she leases out. It was sheep and beef and is now dairy grazing. Flannery did a stint as a board member of Irrigation New Zealand (INZ), the organisation for irrigating farmers. She is adamant she doesn’t want her views described as “irrigator” views — she says she speaks for the community.

Manuherikia Catchment Group

member Mary Flannery.

PHOTO: SUPPLIED

Without irrigation staying the same “we might have deeper water left in the river at Alexandra but if there is not a community, what would be the good of that? We need a good standard of living for everyone, which requires a good income.”

Sole says the MCG does not speak for him, nor other members of environment group COES. COES members are “shell shocked and battle weary” from trying to explain environmental imperatives to irrigators, he says.

“Portraying the community as united is a game the irrigators play — it is hard for people in a small community to speak out against the ‘farming firm’ here. But everyone contributes to society, not just farmers — including people outside these valleys who care about climate emergency and biodiversity. This is an issue of over-abstraction of water, degraded water quality, and land cover changes.”

When the ORC consulted people outside the valleys, there were more people wanting higher flows — and concerns about dairying and large water takes.

Matt Sole (left), of COES, and Nigel Paragreen, of Fish & Game, at the

Manuherikia headwaters above Falls Dam. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Central Otago District Council has produced a report about the economic impact of changing the minimum flow levels. Its findings do not suggest economic calamity if flow levels are raised to 3 cumecs — 58 jobs, directly and indirectly, could be lost in an average-weather year. Contribution to Central Otago’s income could reduce from $27.8 million to $22.6 million.

On a personal level, however, change could be impactful.

MCG chair Anna Gillespie owns Two Farmers Farming with her husband Ben. It is a 400ha farm grazing calves for dairy and beef cattle at Omakau. About 230ha are spray irrigated. The Gillespies’ farm has won a fertiliser firm’s award for environmental effort, which includes a native plant nursery.

Anna and Ben Gillespie of Two Farmers Farming. PHOTO: ALEXIA JOHNSTON

Gillespie uses dramatic language. A minimum flow at Alexandra above 1.1 cumecs would be “catastrophic” and could result in farmers giving up and the community dying. Farmers are “incredibly burnt out and hurt” by disagreement about minimum flow and water allocations. She describes higher minimum flows as “bullshit numbers. There has been arrogance from ORC from the get go. Their policy team will do what they want.”

There has been arrogance from ORC from the get go. Their policy team will do what they want

Proving vocal irrigators are not just cattle farmers, Gary Kelliher farms sheep and deer at Springvale in the Manuherikia valley, sits on the MCG committee — and has remained an ORC councillor throughout the years of wrangling. He is a proud descendent of one of three gold-mining brothers who bought local farms in the 1920s.

“It is staggering that after years we are still miles apart and views entrenched,” Kelliher says. “It has been a waste of time and put people under awful stress. We are in limbo and the situation has been escalated by emotion and ideology. The flow environmentalists want will have a massive detrimental effect on people doing their best and wanting to continue as they are.”

Ben and Vanessa Hore run the 103-year old, 4000ha merino sheep and beef cattle farm at Blackstone Hill north of Omakau. They pull water out of the Manuherikia and store it in two giant 14ha ponds they dug themselves — to “future proof” their investment in spray irrigating 360ha.

“The ponds don’t take away all the risks,” says Mr Hore. “People wanting more water in the river will thump away until they get what they want — they are not prepared to meet halfway.”

The irrigating farmers don’t want to meet halfway, however. They want a minimum flow barely higher than they currently sustain. They are also calling for a bigger Falls Dam, saying more water storage would — in their view appropriately — allow irrigation to continue at its current rate of take and leave more in the river. Falls Dam’s permit expired in 2021 and it has a short-term permit only. “The river has plenty of water, just not stored for when we need it,” says Kelliher. “Water users need a new dam to get better reliability.”

Kelliher’s fellow councillor, Alexa Forbes, is passionate about the environment and responds: “Farmers seem to want some sort of compromise — but that can only be at the expense of the river.”

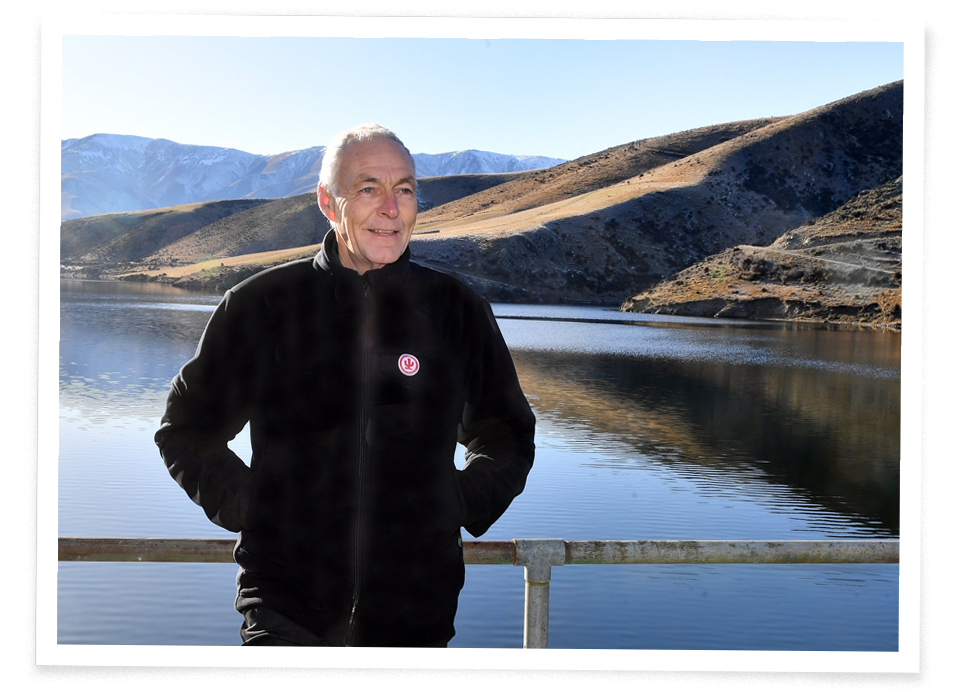

A walk along Falls Dam’s wall, made with uncompacted rubble, does not instill confidence in longevity. A concrete barrier is irregular. It is the responsibility of the dam’s owners — the irrigators — to ensure the dam remains safe.

Roger Williams, Falls Dam manager. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Long-time dam manager Roger Williams, 63, carries out his dam inspection and says “there’s little movement but nothing lasts forever”. His tiny 15-year-old dog, Mila, trots along beside him, shivering against the cold. In winter and spring — when there is snow meltwater — there can be “tremendous amounts of water and no trouble filling the dam,” says Williams.

He supports farmers’ calls for more water storage. “The catchment has ample water for ecological flows and irrigation, but it needs greater storage to achieve this outcome. This can be a win-win scenario for the environment and the economy.”

Fall Dam’s spillway — or ‘‘glory hole’’ — in winter. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Falls Dam was previously owned by the Ministry of Works. Now, irrigating farmers are major shareholders in irrigation companies that own the dams and races. The largest shareholders of Omakau Area Irrigation Company (OAIC) — which owns Falls Dam — reveals dairy farms and cattle grazing farms — among them Wildon Dairy, Satinburn Dairy, Milkwell Holdings (Limerick Downs dairy farm), Manchester Dairy and Kye Farming.

A new Falls Dam, six metres higher, would double the storage and cost $70 million or more. If built lower down, the old dam could be drained into it. There is no fully-fledged savings plan, nor consent, to do this — and farmers talk of a need for public subsidy. The ORC says it has no view on a bigger Falls Dam because no consent request has been lodged.

Nigel Paragreen, from Fish & Game, is an advocate for the environment — but hardly a “thumper”. He would rather collaborate, he says, but agriculture must operate within environmental constraints. Water is a shared resource, not an entitlement. He is happy to chat with Roger Williams at Falls Dam and discuss the undetermined future of water rights. However, he is clear the abstraction is far too much and “if everyone could have agreed a number, it would have happened already”.

Roger Williams (left) and Nigel Paragreen compare notes at Falls Dam.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

“The river is subjected to very low flows due to abstraction over summer,” Paragreen says. “It’s like imposing an extreme drought on the river every year. This creates a bottleneck because habitat has shrunk and lessened in quality. The fish become more stressed and can be difficult to catch. I’ve spoken to anglers who refuse to fish in the summer months because the river gets into such a bad state. If we could alleviate that bottleneck, I think there’s excellent angling potential.”

Whatever flow and allocations the ORC decides, it will then follow the Freshwater Planning Process (FPP). There will be a call for submissions, fed up to the chief freshwater commissioner, a panel convened and its written recommendation sent back to the council — which it can choose to accept or reject. Appeals may follow in the Environment Court or High Court — but only under restricted circumstances.

Council chief executive Richard Saunders acknowledges changes “have an impact on our community and it is only through a collective effort that we will achieve real and lasting change to the quality of freshwater right across our region ... We are committed to reaching a point where the future rules for this catchment are informed by evidence and understood by all.”

The plea is clear — work together and use the facts.

The Manuherikia is a special place and river — its future is reliant on decision making, that must now happen. Paragreen says: “A river shouldn’t need to be special to get base-level protection. The river’s intrinsic value should be reason alone to make sure we’re not causing inappropriate damage. If we’re taking water from the river — any river — we should be doing it in a way that’s sustainable for that water body. On the information seen so far, I think we’re a long way from that here.”

Matt Sole (left), of COES, and Nigel Paragreen, of Fish & Game, at the Manuherikia headwaters above Falls Dam. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Central Otago District Council has produced a report about the economic impact of changing the minimum flow levels. Its findings do not suggest economic calamity if flow levels are raised to 3 cumecs — 58 jobs, directly and indirectly, could be lost in an average-weather year. Contribution to Central Otago’s income could reduce from $27.8 million to $22.6 million.

On a personal level, however, change could be impactful.

MCG chair Anna Gillespie owns Two Farmers Farming with her husband Ben. It is a 400ha farm grazing calves for dairy and beef cattle at Omakau. About 230ha are spray irrigated. The Gillespies’ farm has won a fertiliser firm’s award for environmental effort, which includes a native plant nursery.

Anna and Ben Gillespie of Two Farmers Farming. PHOTO: ALEXIA JOHNSTON

Gillespie uses dramatic language. A minimum flow at Alexandra above 1.1 cumecs would be “catastrophic” and could result in farmers giving up and the community dying. Farmers are “incredibly burnt out and hurt” by disagreement about minimum flow and water allocations. She describes higher minimum flows as “bullshit numbers. There has been arrogance from ORC from the get go. Their policy team will do what they want.”

There has been arrogance from ORC from the get go. Their policy team will do what they want

Proving vocal irrigators are not just cattle farmers, Gary Kelliher farms sheep and deer at Springvale in the Manuherikia valley, sits on the MCG committee — and has remained an ORC councillor throughout the years of wrangling. He is a proud descendent of one of three gold-mining brothers who bought local farms in the 1920s.

“It is staggering that after years we are still miles apart and views entrenched,” Kelliher says. “It has been a waste of time and put people under awful stress. We are in limbo and the situation has been escalated by emotion and ideology. The flow environmentalists want will have a massive detrimental effect on people doing their best and wanting to continue as they are.”

Ben and Vanessa Hore run the 103-year old, 4000ha merino sheep and beef cattle farm at Blackstone Hill north of Omakau. They pull water out of the Manuherikia and store it in two giant 14ha ponds they dug themselves — to “future proof” their investment in spray irrigating 360ha.

“The ponds don’t take away all the risks,” says Mr Hore. “People wanting more water in the river will thump away until they get what they want — they are not prepared to meet halfway.”

The irrigating farmers don’t want to meet halfway, however. They want a minimum flow barely higher than they currently sustain. They are also calling for a bigger Falls Dam, saying more water storage would — in their view appropriately — allow irrigation to continue at its current rate of take and leave more in the river. Falls Dam’s permit expired in 2021 and it has a short-term permit only. “The river has plenty of water, just not stored for when we need it,” says Kelliher. “Water users need a new dam to get better reliability.”

Kelliher’s fellow councillor, Alexa Forbes, is passionate about the environment and responds: “Farmers seem to want some sort of compromise — but that can only be at the expense of the river.”

A walk along Falls Dam’s wall, made with uncompacted rubble, does not instill confidence in longevity. A concrete barrier is irregular. It is the responsibility of the dam’s owners — the irrigators — to ensure the dam remains safe.

Roger Williams, Falls Dam manager.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Long-time dam manager Roger Williams, 63, carries out his dam inspection and says “there’s little movement but nothing lasts forever”. His tiny 15-year-old dog, Mila, trots along beside him, shivering against the cold. In winter and spring — when there is snow meltwater — there can be “tremendous amounts of water and no trouble filling the dam,” says Williams.

He supports farmers’ calls for more water storage. “The catchment has ample water for ecological flows and irrigation, but it needs greater storage to achieve this outcome. This can be a win-win scenario for the environment and the economy.”

Fall Dam’s spillway — or ‘‘glory hole’’ — in winter. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Falls Dam was previously owned by the Ministry of Works. Now, irrigating farmers are major shareholders in irrigation companies that own the dams and races. The largest shareholders of Omakau Area Irrigation Company (OAIC) — which owns Falls Dam — reveals dairy farms and cattle grazing farms — among them Wildon Dairy, Satinburn Dairy, Milkwell Holdings (Limerick Downs dairy farm), Manchester Dairy and Kye Farming.

A new Falls Dam, six metres higher, would double the storage and cost $70 million or more. If built lower down, the old dam could be drained into it. There is no fully-fledged savings plan, nor consent, to do this — and farmers talk of a need for public subsidy. The ORC says it has no view on a bigger Falls Dam because no consent request has been lodged.

Nigel Paragreen, from Fish & Game, is an advocate for the environment — but hardly a “thumper”. He would rather collaborate, he says, but agriculture must operate within environmental constraints. Water is a shared resource, not an entitlement. He is happy to chat with Roger Williams at Falls Dam and discuss the undetermined future of water rights. However, he is clear the abstraction is far too much and “if everyone could have agreed a number, it would have happened already”.

Roger Williams (left) and Nigel Paragreen compare notes at Falls Dam. PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

“The river is subjected to very low flows due to abstraction over summer,” Paragreen says. “It’s like imposing an extreme drought on the river every year. This creates a bottleneck because habitat has shrunk and lessened in quality. The fish become more stressed and can be difficult to catch. I’ve spoken to anglers who refuse to fish in the summer months because the river gets into such a bad state. If we could alleviate that bottleneck, I think there’s excellent angling potential.”

Whatever flow and allocations the ORC decides, it will then follow the Freshwater Planning Process (FPP). There will be a call for submissions, fed up to the chief freshwater commissioner, a panel convened and its written recommendation sent back to the council — which it can choose to accept or reject. Appeals may follow in the Environment Court or High Court — but only under restricted circumstances.

Council chief executive Richard Saunders acknowledges changes “have an impact on our community and it is only through a collective effort that we will achieve real and lasting change to the quality of freshwater right across our region ... We are committed to reaching a point where the future rules for this catchment are informed by evidence and understood by all.”

The plea is clear — work together and use the facts.

The Manuherikia is a special place and river — its future is reliant on decision making, that must now happen. Paragreen says: “A river shouldn’t need to be special to get base-level protection. The river’s intrinsic value should be reason alone to make sure we’re not causing inappropriate damage. If we’re taking water from the river — any river — we should be doing it in a way that’s sustainable for that water body. On the information seen so far, I think we’re a long way from that here.”