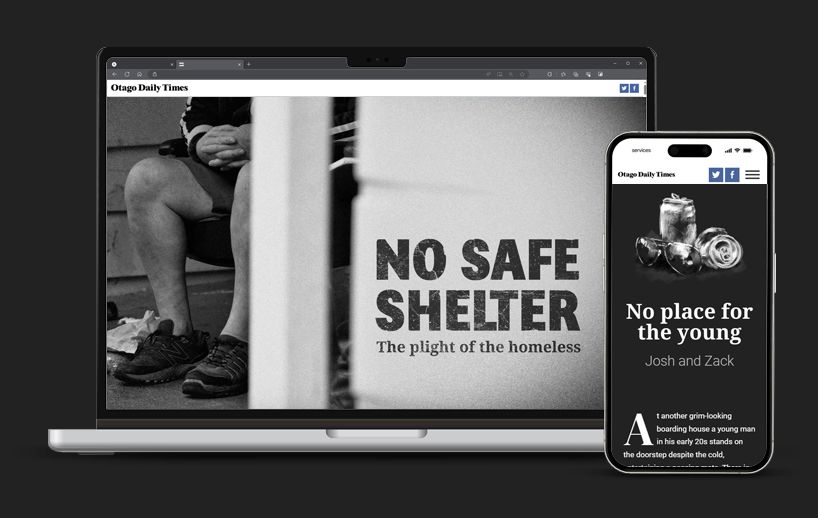

Social affairs journalism requires watching sadness from the sidelines. But what if rescue doesn’t come? As part of her homelessness investigation, Mary Williams met a young person who fell between the cracks of care. This is her story of crossing the line between journalist and youth advocate.

Social affairs journalism requires watching sadness from the sidelines. But what if rescue doesn’t come? As part of her homelessness investigation, Mary Williams met a young person who fell between the cracks of care. This is her story of crossing the line between journalist and youth advocate.

WHEN a homeless teenager with no family asks ‘‘can I live with you?’’ it feels the hardest question.

‘‘No. Sorry, Harry. I’m a journalist. My job is to tell stories like yours.’’

But during my short time walking alongside Harry on his hellish road of homelessness, help was needed — and there was no-one to give it.

I have held his sick bucket and spoken up for him.

Who wouldn’t?

In late August, during my investigation into Dunedin’s homeless crisis, the night shelter called.

‘‘We have a teenager here. It really feels the worst.’’

I met Harry in the mall.

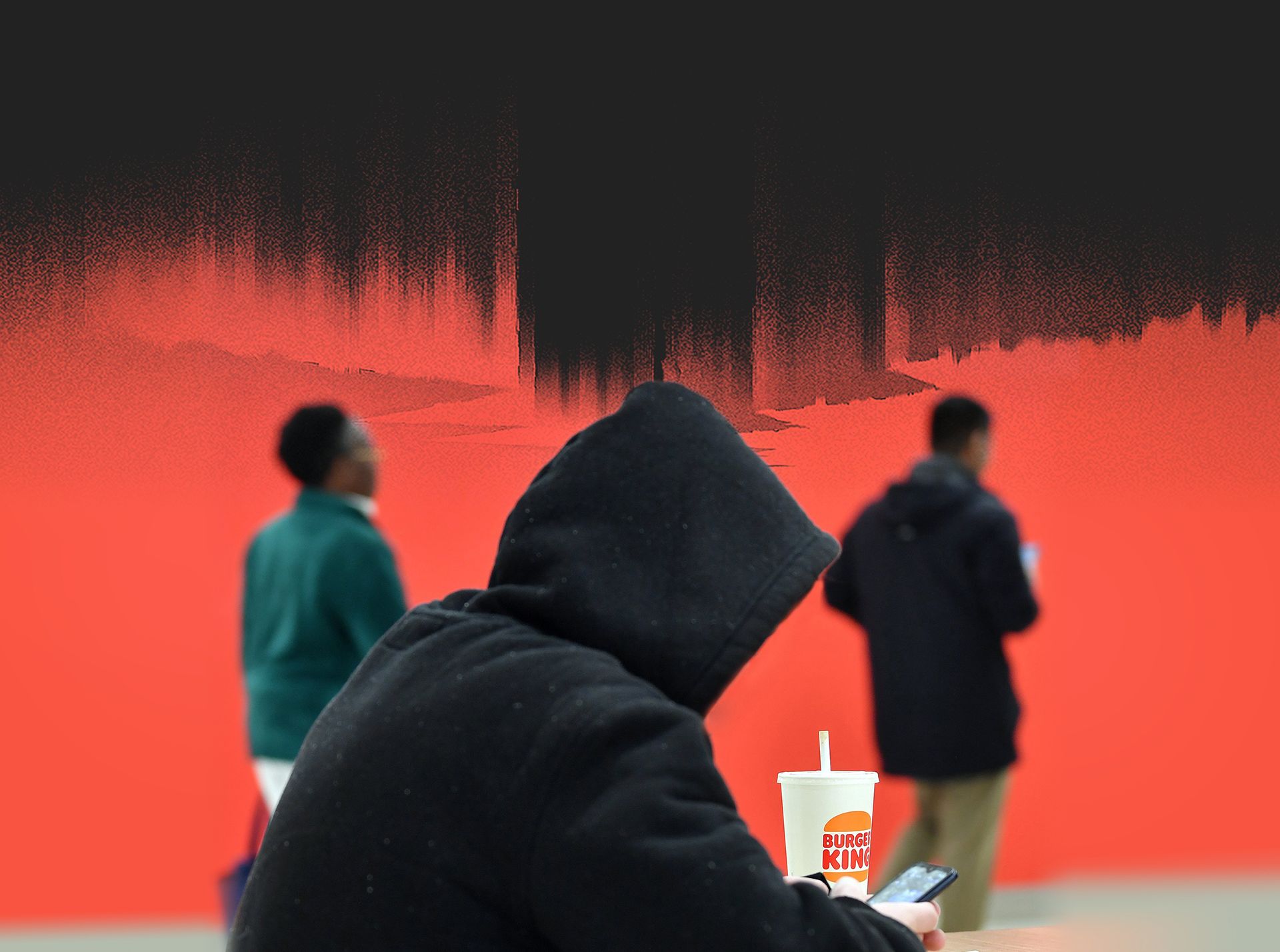

Hidden by his hoodie, elbows on the plastic table, he was bored and playing with a smartphone.

He’d blown his money on it, understandably — it was a lifeline to friends.

There was no money left — and only the shelter to go to.

Harry cuts a waif-like figure.

When he arrived at the shelter, staff thought he was 16 but felt he was behaving younger — maybe 12.

Harry is 18 and has ‘‘aged out of care’’, as the government’s child agency Oranga Tamariki puts it.

‘‘How are you?’’ I asked.

Harry offered up puppy eyes and a handshake. ‘‘I’m all right. Yourself?’’

Harry wasn’t all right.

He’d been cared for by staff in a residential disability service throughout his adolescence.

Having a birthday hadn’t changed his needs.

Yet his world had shifted — from a managed environment to a world of no rules and no home.

It had been a chaotic period.

Various sources have confirmed Harry was put up in a low-budget motel.

He found himself falling under the influence of other people, risky situations and trouble.

But unlike a teenager with family to turn to, Harry was alone.

There was no parental home to go to for a Sunday feed, to get his washing done, chat about life choices or just cuddle the cat.

He had ended up at the shelter.

Harry yawned — a lot.

I asked if he was ill, on drugs, or maybe had a hangover.

His answers were off the record and may or may not have been true.

One thing was certain — Harry faced risk.

He had ideas about a job he wanted to train for — but said ‘‘I am scared of what might happen next”.

He gave me consent to talk to people about his life, including the government — and a foster mum who cared for him before the disability service.

WHEN a homeless teenager with no family asks ‘‘can I live with you?’’ it feels the hardest question.

‘‘No. Sorry, Harry. I’m a journalist. My job is to tell stories like yours.’’

But during my short time walking alongside Harry on his hellish road of homelessness, help was needed — and there was no-one to give it.

I have held his sick bucket and spoken up for him.

Who wouldn’t?

In late August, during my investigation into Dunedin’s homeless crisis, the night shelter called.

‘‘We have a teenager here. It really feels the worst.’’

I met Harry in the mall.

Hidden by his hoodie, elbows on the plastic table, he was bored and playing with a smartphone.

He’d blown his money on it, understandably — it was a lifeline to friends.

There was no money left — and only the shelter to go to.

Harry cuts a waif-like figure.

When he arrived at the shelter, staff thought he was 16 but felt he was behaving younger — maybe 12.

Harry is 18 and has ‘‘aged out of care’’, as the government’s child agency Oranga Tamariki puts it.

‘‘How are you?’’ I asked.

Harry offered up puppy eyes and a handshake. ‘‘I’m all right. Yourself?’’

Harry wasn’t all right.

He’d been cared for by staff in a residential disability service throughout his adolescence.

Having a birthday hadn’t changed his needs.

Yet his world had shifted — from a managed environment to a world of no rules and no home.

It had been a chaotic period.

Various sources have confirmed Harry was put up in a low-budget motel.

He found himself falling under the influence of other people, risky situations and trouble.

But unlike a teenager with family to turn to, Harry was alone.

There was no parental home to go to for a Sunday feed, to get his washing done, chat about life choices or just cuddle the cat.

He had ended up at the shelter.

Harry yawned — a lot.

I asked if he was ill, on drugs, or maybe had a hangover.

His answers were off the record and may or may not have been true.

One thing was certain — Harry faced risk.

He had ideas about a job he wanted to train for — but said ‘‘I am scared of what might happen next”.

He gave me consent to talk to people about his life, including the government — and a foster mum who cared for him before the disability service.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Harry’s foster mum sounded relieved to hear about Harry, but had ‘‘big concerns’’ about his future.

She called for urgent action.

‘‘He needs all the help he can be given, so he is not just another statistic.

‘‘He’s been micro-managed and medicated.

‘‘We cannot sit back and let a situation now unfold.

‘‘If society says ‘see you later’, he could self-destruct quite quickly.’’

She talked about health assessments in the past, but was unsure of later, confirmed diagnoses — if any.

The Oranga Tamariki statement of rights says ‘‘if you are leaving care because you are over 18, but would rather stay with a caregiver, you have the right to live with a caregiver until 21’’.

It also says Oranga Tamariki can give advice and assistance up to the age of 25.

The disability service where Harry lived says it guides young people with special needs towards positive adult lives with skills they need to live well.

It all sounded good, but didn’t sound like Harry’s case.

Nearly all young people ageing out of care — 96% — choose to leave their care provider.

Both the disability service and Oranga Tamariki indicated Harry had turned down help offered by them.

Oranga Tamariki regional manager Christine McKenna said Harry’s situation was ‘‘deeply concerning’’, and acknowledged Harry ‘‘has limited wider support available’’.

The disability service said it was challenging, when a young person ‘‘disengaged’’ when there could be a need for ‘‘support for that person to live independently and safely’’.

Oranga Tamariki said, regardless, it was ‘‘engaged with other agencies in the city to try and provide the support that Harry needs’’.

Ms McKenna said her staff in Dunedin ‘‘care deeply about him and all want the best for him’’.

That was at the end of August.

The night shelter is not daycare for teenagers with needs.

A small charity, it is open from 6pm to 9am.

During the day, its occupants must survive on the streets.

After five nights of free food and a warm bed, they must leave.

The shelter made an exception for Harry.

It extended his stay, and reached out to other charities, in the hope support and a home would materialise.

But when I next visited Harry at the shelter, no help had arrived.

Harry’s smartphone had also disappeared — lost or stolen.

He watched cartoons on the TV, sucked on a lolly and asked if he could come and spend the day with me.

I said ‘‘sorry, no’’. It was troubling.

By mid-September, there was still no plan.

Worse, Harry had got sick — and then disappeared.

Harry had suffered a seizure at the night shelter and the staff had called an ambulance.

Harry had recovered, but the cause was unknown.

The next day, he had gone to live with a woman he had met at the bus hub.

It sounded weird — who was she?

There was nothing the shelter staff could do. Harry was 18.

A few days later, I was at the hospital for unconnected reasons and Harry appeared: ‘‘Hello Mary’’.

Hot on his heels was a 40-something, thin woman: ‘‘He’s been having fits,’’ she said.

The woman was quickly surrounded by hospital security staff.

They served her a trespass notice and said ‘‘you know you are not allowed here’’.

She turned to Harry before being bundled into a police car.

Speaking in a stressed tone, she said ‘‘sorry, I have my own issues’’.

On a later day, I met up with the woman where she lived, to get the backstory.

It was a dimly lit, shared house.

She told me about her own challenges, including addiction to ‘‘the grog’’, an assault and time she had spent homeless — in shelters and on the street.

‘‘But you’re not going to turn this into a story about me, are you?’’

No. This was a story about Harry and the support and home he needs — which wasn’t to be found here.

From her stories, it seemed Harry’s time here had not been risk free.

Alcohol and drugs were in circulation — not supplied by her, she said.

Two other homeless males had also stayed — one younger than Harry.

There was a time when Harry turned up in the middle of the night, claiming he had been threatened with a gun, she said.

‘‘What sort of a person shuts the door on young people with nowhere to go?

‘‘I couldn’t stand the idea of kids walking the streets.’’

It turns out those door-shutters included me.

Back in the hospital, Harry had asked me ‘‘can I live with you?’’

No, he couldn’t — but leaving Harry to fend for himself again was clearly not an option.

I called the night shelter.

Acting above and beyond the charity’s remit, the shelter’s community worker Chris Edwards took Harry to Work and Income and demanded safe housing, flagging Harry’s situation and the need to contact Oranga Tamariki.

Work and Income put Harry in a George St motel room — on his own.

That evening, Harry vomited — and the motel owner took him to hospital.

Harry made his own way back and I visited him at the motel, along with Mr Edwards.

No-one had cleaned up his sick, so I did.

I interviewed them both. ‘‘Unless Harry has the appropriate support put in place, his future looks dark," Mr Edwards said.

‘‘He has no ability to look after himself or discern people who are good or bad for him, or stop things being stolen off him.

‘‘The list of his needs is tremendously long.’’

I asked Harry what he wanted.

‘‘It was all boundaries at the boys’ home.

‘‘I want freedom.

‘‘But I need help doing all the normal stuff, looking after money, eating the right things, getting training for a job.’’

He said he thought he had been ‘‘manipulated’’ by some people.

‘‘I feel tired from all the moving around,’’ Harry said.

He asked me again: ‘‘Can I come home with you?’’

No, he couldn’t. Sorry.

On the third night, he tried to kill himself.

PHOTO: STEPHEN JAQUIERY

Harry’s foster mum sounded relieved to hear about Harry, but had ‘‘big concerns’’ about his future.

She called for urgent action.

‘‘He needs all the help he can be given, so he is not just another statistic.

‘‘He’s been micro-managed and medicated.

‘‘We cannot sit back and let a situation now unfold.

‘‘If society says ‘see you later’, he could self-destruct quite quickly.’’

She talked about health assessments in the past, but was unsure of later, confirmed diagnoses — if any.

The Oranga Tamariki statement of rights says ‘‘if you are leaving care because you are over 18, but would rather stay with a caregiver, you have the right to live with a caregiver until 21’’.

It also says Oranga Tamariki can give advice and assistance up to the age of 25.

The disability service where Harry lived says it guides young people with special needs towards positive adult lives with skills they need to live well.

It all sounded good, but didn’t sound like Harry’s case.

Nearly all young people ageing out of care — 96% — choose to leave their care provider.

Both the disability service and Oranga Tamariki indicated Harry had turned down help offered by them.

Oranga Tamariki regional manager Christine McKenna said Harry’s situation was ‘‘deeply concerning’’, and acknowledged Harry ‘‘has limited wider support available’’.

The disability service said it was challenging, when a young person ‘‘disengaged’’ when there could be a need for ‘‘support for that person to live independently and safely’’.

Oranga Tamariki said, regardless, it was ‘‘engaged with other agencies in the city to try and provide the support that Harry needs’’.

Ms McKenna said her staff in Dunedin ‘‘care deeply about him and all want the best for him’’.

That was at the end of August.

The night shelter is not daycare for teenagers with needs.

A small charity, it is open from 6pm to 9am.

During the day, its occupants must survive on the streets.

After five nights of free food and a warm bed, they must leave.

The shelter made an exception for Harry.

It extended his stay, and reached out to other charities, in the hope support and a home would materialise.

But when I next visited Harry at the shelter, no help had arrived.

Harry’s smartphone had also disappeared — lost or stolen.

He watched cartoons on the TV, sucked on a lolly and asked if he could come and spend the day with me.

I said ‘‘sorry, no’’. It was troubling.

By mid-September, there was still no plan.

Worse, Harry had got sick — and then disappeared.

Harry had suffered a seizure at the night shelter and the staff had called an ambulance.

Harry had recovered, but the cause was unknown.

The next day, he had gone to live with a woman he had met at the bus hub.

It sounded weird — who was she?

There was nothing the shelter staff could do. Harry was 18.

A few days later, I was at the hospital for unconnected reasons and Harry appeared: ‘‘Hello Mary’’.

Hot on his heels was a 40-something, thin woman: ‘‘He’s been having fits,’’ she said.

The woman was quickly surrounded by hospital security staff.

They served her a trespass notice and said ‘‘you know you are not allowed here’’.

She turned to Harry before being bundled into a police car.

Speaking in a stressed tone, she said ‘‘sorry, I have my own issues’’.

On a later day, I met up with the woman where she lived, to get the backstory.

It was a dimly lit, shared house.

She told me about her own challenges, including addiction to ‘‘the grog’’, an assault and time she had spent homeless — in shelters and on the street.

‘‘But you’re not going to turn this into a story about me, are you?’’

No. This was a story about Harry and the support and home he needs — which wasn’t to be found here.

From her stories, it seemed Harry’s time here had not been risk free.

Alcohol and drugs were in circulation — not supplied by her, she said.

Two other homeless males had also stayed — one younger than Harry.

There was a time when Harry turned up in the middle of the night, claiming he had been threatened with a gun, she said.

‘‘What sort of a person shuts the door on young people with nowhere to go?

‘‘I couldn’t stand the idea of kids walking the streets.’’

It turns out those door-shutters included me.

Back in the hospital, Harry had asked me ‘‘can I live with you?’’

No, he couldn’t — but leaving Harry to fend for himself again was clearly not an option.

I called the night shelter.

Acting above and beyond the charity’s remit, the shelter’s community worker Chris Edwards took Harry to Work and Income and demanded safe housing, flagging Harry’s situation and the need to contact Oranga Tamariki.

Work and Income put Harry in a George St motel room — on his own.

That evening, Harry vomited — and the motel owner took him to hospital.

Harry made his own way back and I visited him at the motel, along with Mr Edwards.

No-one had cleaned up his sick, so I did.

I interviewed them both. ‘‘Unless Harry has the appropriate support put in place, his future looks dark," Mr Edwards said.

‘‘He has no ability to look after himself or discern people who are good or bad for him, or stop things being stolen off him.

‘‘The list of his needs is tremendously long.’’

I asked Harry what he wanted.

‘‘It was all boundaries at the boys’ home.

‘‘I want freedom.

‘‘But I need help doing all the normal stuff, looking after money, eating the right things, getting training for a job.’’

He said he thought he had been ‘‘manipulated’’ by some people.

‘‘I feel tired from all the moving around,’’ Harry said.

He asked me again: ‘‘Can I come home with you?’’

No, he couldn’t. Sorry.

On the third night, he tried to kill himself.

Emergency services were called in time.

I visited Harry in hospital.

‘‘I was sick of this life,’’ he said.

I asked him what he liked.

He mentioned McDonald’s and laser tag.

Harry signed a note I scribbled, saying I could advocate for him, until professional help came along — this time.

It was an unusual position for a journalist to be in — but it felt temporarily necessary.

I contacted Oranga Tamariki (OT) and the Ministry of Social Development (MSD) — again.

OT’s response promised nothing.

It said it would ‘‘make sure the right local people are aware’’.

It advised I could lodge a formal concern about Harry with its ‘‘transitional’’ team.

I did. I asked how OT had helped Harry since I first contacted them.

They did not answer.

MSD said it was ‘‘really concerned’’, but added ‘‘we cannot provide or impose supervised care. Legislation gives us no role in that area.’’

It had provided the motel room because ‘‘it’s important he was not left to sleep rough’’.

‘‘We will continue to work with Harry to understand his needs and support him alongside other agencies.’’

I contacted a leading social care charity head, and asked the chances of a homeless young person getting a longer stay in hospital after a suicide attempt, to assess their mental health and give time to arrange supported living.

Their answer was ‘‘unlikely’’.

The pressure on mental health services is huge, they said.

People who are a threat to others — or have a clear plan for killing themselves — are prioritised.

That didn’t sound like Harry.

Harry’s luck, however, seemed to change the next morning.

There is no way of telling if this was influenced by media interest.

A psychiatrist breezed by Harry’s hospital bed and said it was unacceptable he had been ‘‘living at the shelter’’.

A transfer to another ward would happen when he was physically well enough.

It was a moment of relief.

Could this lead to the supported housing Harry needed?

I suggested Harry might want to talk to his foster mum, for reassurance.

He rang her on my phone. It was a calm and loving conversation.

I called another charity and asked if a social worker could advocate for Harry — so I could step down.

It said yes. Its social worker quickly came to the hospital and helped reassure Harry that staying in hospital was the best thing for him.

Some young school friends of Harry’s arrived. Their influence was positive.

But even here, Harry was prey to others — and things took a dark turn, fast.

A man in his early 20s turned up at lunchtime, with a teenager, in filthy clothes, in tow.

I asked the man his name.

He claimed he was Harry’s brother. He wasn’t.

He said he’d informed the hospital he was the next of kin. He wasn’t.

He got agitated.

‘‘I’m not on the system, I’m homeless.

‘‘I am going to find a boarding house real soon ... I have been kicked out by my own mother.’’

The man then talked fast at Harry, persuading him to get out of bed and get ready to leave.

Harry put on his shoes. Time seemed to speed up.

I left his bedside and told a nurse. They called security.

The same security men who had extricated Harry from the woman a few days before now turned to me: ‘‘Should these people be escorted out?’’ I gave a firm ‘‘yes’’.

I later discovered the two males who tried to get Harry to leave hospital were the same people who lived in the woman’s shared house with Harry. It was unsurprising.

When asked how it had helped Harry since the end of August, Oranga Tamariki said it was ‘‘a very sad situation’’, but otherwise clammed up.

It had ‘‘nothing further to add’’ at this stage.

Harry was once again reassured of the value of staying in hospital.

It felt touch and go, but he did stay — and was moved to a mental health ward at Wakari.

A month passed. Harry and I waited patiently to hear the plan.

Multiple agencies — our health service, Oranga Tamariki, the Ministry of Social Development and more than one local charity — knew about Harry. They also knew the ODT knew about Harry. Surely, there would be a happy ending?

I visited Harry yesterday. He was excited to tell me his news.

He was being discharged — he thought to supported housing. A social worker was going to pick up his cuddly toys and posters from the disability service.

He was wrong.

The only ‘‘plan’’ was to discharge him to the night shelter.

I rang his foster mum. ‘‘Outrageous and inhumane,’’ she said.

‘‘How can they? Harry is not an animal to leave at the SPCA. If they discharge him with nowhere to go, it is throwing him to the wolves.’’

Emergency services were called in time.

I visited Harry in hospital.

‘‘I was sick of this life,’’ he said.

I asked him what he liked.

He mentioned McDonald’s and laser tag.

Harry signed a note I scribbled, saying I could advocate for him, until professional help came along — this time.

It was an unusual position for a journalist to be in — but it felt temporarily necessary.

I contacted Oranga Tamariki (OT) and the Ministry of Social Development (MSD) — again.

OT’s response promised nothing.

It said it would ‘‘make sure the right local people are aware’’.

It advised I could lodge a formal concern about Harry with its ‘‘transitional’’ team.

I did. I asked how OT had helped Harry since I first contacted them.

They did not answer.

MSD said it was ‘‘really concerned’’, but added ‘‘we cannot provide or impose supervised care. Legislation gives us no role in that area.’’

It had provided the motel room because ‘‘it’s important he was not left to sleep rough’’.

‘‘We will continue to work with Harry to understand his needs and support him alongside other agencies.’’

I contacted a leading social care charity head, and asked the chances of a homeless young person getting a longer stay in hospital after a suicide attempt, to assess their mental health and give time to arrange supported living.

Their answer was ‘‘unlikely’’.

The pressure on mental health services is huge, they said.

People who are a threat to others — or have a clear plan for killing themselves — are prioritised.

That didn’t sound like Harry.

Harry’s luck, however, seemed to change the next morning.

There is no way of telling if this was influenced by media interest.

A psychiatrist breezed by Harry’s hospital bed and said it was unacceptable he had been ‘‘living at the shelter’’.

A transfer to another ward would happen when he was physically well enough.

It was a moment of relief.

Could this lead to the supported housing Harry needed?

I suggested Harry might want to talk to his foster mum, for reassurance.

He rang her on my phone. It was a calm and loving conversation.

I called another charity and asked if a social worker could advocate for Harry — so I could step down.

It said yes. Its social worker quickly came to the hospital and helped reassure Harry that staying in hospital was the best thing for him.

Some young school friends of Harry’s arrived. Their influence was positive.

But even here, Harry was prey to others — and things took a dark turn, fast.

A man in his early 20s turned up at lunchtime, with a teenager, in filthy clothes, in tow.

I asked the man his name.

He claimed he was Harry’s brother. He wasn’t.

He said he’d informed the hospital he was the next of kin. He wasn’t.

He got agitated.

‘‘I’m not on the system, I’m homeless.

‘‘I am going to find a boarding house real soon ... I have been kicked out by my own mother.’’

The man then talked fast at Harry, persuading him to get out of bed and get ready to leave.

Harry put on his shoes. Time seemed to speed up.

I left his bedside and told a nurse. They called security.

The same security men who had extricated Harry from the woman a few days before now turned to me: ‘‘Should these people be escorted out?’’ I gave a firm ‘‘yes’’.

I later discovered the two males who tried to get Harry to leave hospital were the same people who lived in the woman’s shared house with Harry. It was unsurprising.

When asked how it had helped Harry since the end of August, Oranga Tamariki said it was ‘‘a very sad situation’’, but otherwise clammed up.

It had ‘‘nothing further to add’’ at this stage.

Harry was once again reassured of the value of staying in hospital.

It felt touch and go, but he did stay — and was moved to a mental health ward at Wakari.

A month passed. Harry and I waited patiently to hear the plan.

Multiple agencies — our health service, Oranga Tamariki, the Ministry of Social Development and more than one local charity — knew about Harry. They also knew the ODT knew about Harry. Surely, there would be a happy ending?

I visited Harry yesterday. He was excited to tell me his news.

He was being discharged — he thought to supported housing. A social worker was going to pick up his cuddly toys and posters from the disability service.

He was wrong.

The only ‘‘plan’’ was to discharge him to the night shelter.

I rang his foster mum. ‘‘Outrageous and inhumane,’’ she said.

‘‘How can they? Harry is not an animal to leave at the SPCA. If they discharge him with nowhere to go, it is throwing him to the wolves.’’

Editorial:

When the line blurs between journalist and advocate

It should never be like this.

A lost, homeless teenager, alone on the streets of Dunedin, desperately in need of compassion and direction.

A journalist forced to break the fourth wall of the Fourth Estate to provide help when nobody else did.

Today we bring you Harry’s story.

Journalists generally remain apart from events. As independent, “fly-on-the-wall” observers, they strive to see all sides of an issue and give everyone the same opportunities to have their say.

Before the rise of social media, relentless online deadlines and clickbait, reporters were never meant, or encouraged by newsroom bosses, to become part of the story.

But life is never that simple. A generation of Christchurch journalists realised how difficult it was to remain objective while living through the earthquakes which damaged their homes, wrecked their city and killed friends and colleagues.

Despite remaining as detached as possible throughout her series on Dunedin housing and homelessness, investigative ODT journalist Mary Williams found herself in the extraordinary position of advocating for teenager Harry, who has slipped through the cracks of state care.

Oranga Tamariki said late in August that Harry, 18, had turned down offers of help and that it was “deeply concerning”.

Recently, after Ms Williams briefly became Harry’s advocate, the agency offered no help and advised she could lodge a formal concern, which she did.

Very few of us can imagine the agonies and insecurities Harry and others experience as they bounce from one bed to another like a marble in a pinball machine, with a sense of never belonging anywhere and that nobody really cares.

Harry’s story is not totally one of departmental dogmatism and bureaucratic bungling. There have been kind and generous people along the way, as there usually are.

But if it’s true that a society is only as good as the way it treats its most vulnerable, then clearly we are failing.

When it comes to Harry and the too-many other Harrys around New Zealand, we believe Oranga Tamariki and the Ministry of Social Development have been lackadaisical and uncaring in their duty of care.

Would it to be too much to hope the incoming government might take up the cudgels for Harrys everywhere?

Whether or not it does, these agencies need to take a long hard look at how they act, remember their reason for being and, if the cap fits, reconnect with their humanity.

Page design: Mathew Patchett